Tabular typesetting is the most complex and time-consuming

of all textual features to get right. This holds true whether

you are using cold or hot metal type, typing in plaintext form,

using a typewriter or a wordprocessor, using

LATEX, using HTML or

XML, using a DTP

system, or some other text-handling package.

Printers charge extra when you ask them to typeset tables,

and they do so for good reason:

Each table tends to have its own peculiarities,

so it’s necessary to give some thought to each one,

and to fiddle with the alternative approaches

until finding something that looks good and

communicates well.

(Knuth, 1986, ch.22)

Fortunately, LATEX provides a table model with a mixture

of defaults and configurability to let it produce very high

quality tables with a minimum of effort. There are two things

you need to know before you start: one is the terminology

(see the sidebar ‘Terminology for tables and figures’ below) and the other is what

‘floats’ are (see

§ 4.2.1 below

The grid alignment of information in rows and columns

in a Table is

called a ‘tabulation’ or

‘tabular matter’, done with a

tabular environment, and we’ll deal

with that in § 4.2.3 below.

4.2.1 Floats

Tables and Figures (and several other features of

documents like sidebars, panels, warnings, tips, examples,

and exercises) are what printers and publishers call

‘Floats’.

Floats are not part of the normal stream of

your text, but separate freestanding entities, so they can

be positioned in a part of the page to themselves (top,

middle, bottom, left, right, or wherever the layout designer

has specified). They always have a caption describing them

and they are always numbered so they can be referred to from

elsewhere in the text.

Formatted pages (as in print and

PDFs) are a fixed size, so LATEX

automatically moves Floats to the nearest available space,

depending on a ) how much space is left on the page at the point

that they are processed and b ) any recommendations you make in the options to the

figure or table (or other)

environment. If there is not enough room on the current

page, the float is moved to the top of the next page.

Please read the preceding

paragraph again.

The float package can be used to

create new types of float, like the sidebars, panels,

warnings, tips, examples, and exercises mentioned above.

When we talk below about Tables and Figures, the same

applies to any new type of float you create with the

float package.

4.2.1.1 Moving floats

What to do if the floats aren't positioned sensibly?

Warning

Never try to move your floats around until

after you have finished writing and

editing. They will be perfectly safe in draft mode until

then, so stop worrying.

The reason is that if you prematurely re-position a

float, sure as anything you'll need to edit the

surrounding text, or even the text many pages before,

and that will change the layout, just meaning extra

work.

The positioning can be changed by several means:

Move the table or

figure environment to an earlier or

later point in the section. Sometimes just moving it

to between the preceding or following paragraph will

make it float to a more acceptable position.

Use the optional argument to the

table or figure

environment. This can be any mix of the letters

h (‘here’),

t (‘top’),

b (‘bottom’),

p (‘on a page by

itself’) to suggest

to LATEX where the Table or Figure should go

if possible (order is not

significant: LATEX will pick the best fit).

To make your recommendation stronger, precede the

first letter with an exclamation mark

(!). Do not omit the p (it

SHOULD be present for

all large floats), otherwise your float may be omitted

because it doesn't fit, and moved to the end of the

section, chapter, or document for you to decide on a

better layout.

In this example you can see a Table requested to

go here(!) or at the top of the page; and a Figure

requested to go at the bottom of the page or on the

next full page by itself.

\begin{table}[!ht]

...

\end{table}

\begin{figure}[bp]

...

\end{figure}Try loosening the settings that control how many

floats are allowed per page (at the top and bottom

separately, and overall) and how much of the page they

can take up. The settings are:

\setcounter{topnumber}{9}

\setcounter{bottomnumber}{9}

\setcounter{totalnumber}{20}

\setcounter{dbltopnumber}{9}

\renewcommand{\topfraction}{.85}

\renewcommand{\bottomfraction}{.7}

\renewcommand{\textfraction}{.15}

\renewcommand{\floatpagefraction}{.66}

\renewcommand{\dbltopfraction}{.66}

\renewcommand{\dblfloatpagefraction}{.66}The ones beginning with dbl are for

use with LATEX's built-in double-column mode.

If the float almost fits, you can use

\enlargethispace{\baselineskip} to

allow the page to be one line longer than normal.

The \raggedbottom command will

allow the page to place all unused space at the

bottom, rather than between paragraphs. This can act

as a temporary fix but is not recommended for serious

work. In addition, most publishers will not accept

pages with large amounts blank at the bottom;

You may be able to cause a premature page-break

enough to fit the misplaced float, but use

\clearpage, not

\newpage or

\pagebreak, because

\clearpage takes account of floats,

if it can, wherease the other two commands do

not;

If you are unable to arrange things easily, as a

last resort you can use the float

package and the option letter capital H

(‘Here, dammit!’).

Be aware that Figures or Tables using this option

will no longer be Floats so the

onus is on you to ensure that the numbering sequence

is not disrupted.

There are other good suggestions in the TEX

FAQ at

https://texfaq.org/FAQ-floats.

Remember that if there really, really is not enough

space ‘here’ on the page, then it

really, really won’t fit, and you

will HAVE TO move things

elsewhere, or change your text.

4.2.1.2 Avoiding too many Floats

Authors sometimes want many figures or tables

occurring in rapid succession, which is poor writing, as

it’s not just unfair to the reader, but raises the problem

of how they are going to fit on the page and still leave

room for text. In extreme cases, LATEX will give up

trying, and stack them all up until the end of the chapter

or section for you to decide manually where to put

them.

The skill is to space your tables and figures out

within your text so that they intrude neither on the

thread of your argument or discussion, nor on the visual

balance of the typeset pages. But this is a skill few

authors have, and it’s one point at which professional

typographic advice or manual intervention may be

needed.

Please now read this section a second time. Getting

the hang of floats can take a while if you’ve never come

across the idea before. Most writers strongly recommend

writing the document in its entirety first, and not

worrying about where the floats end up until the text is

complete and not likely to change any more.

Then start moving any floats that are

misplaced.

4.2.3 Simple tabular matter

To typeset the grid within a table

(or elsewhere), you use

the tabular environment.

There are four ways to enter the data:

- By hand

you can enter the tabular matter (cell data) by

typing it in, which is perhaps the most common

method, especially for small quantities of data;

- In a grid tool

many LATEX editors come with a pop-up grid tool

like a miniature spreadsheet, which makes creating

tabular matter easier, at the cost of some loss of

fine control (see Figure 4.1 below).

- With a package

if the quantity of data is very large and is

already in a spreadsheet or database, or if it is data

which will change frequently before you are

finished your document,

you can use the datatool package

(formerly known as csvtools) to

read the data from a

Comma-Separated Values (CSV) spreadsheet import/export file

(see § 4.2.4 below). If the data changes,

you just re-export it and re-run LATEX.

For large numbers of tables in big documents

(eg theses) this is by far the most accurate and

time-saving method.

- As an image

it is also possible to include a

‘table’ which has actually been

captured as an image from elsewhere, such as a

screenshot from a spreadsheet (so it’s not really a table

just a picture of one). We will see how to include images in

§ 4.3 below on Figures, where they are

more common.

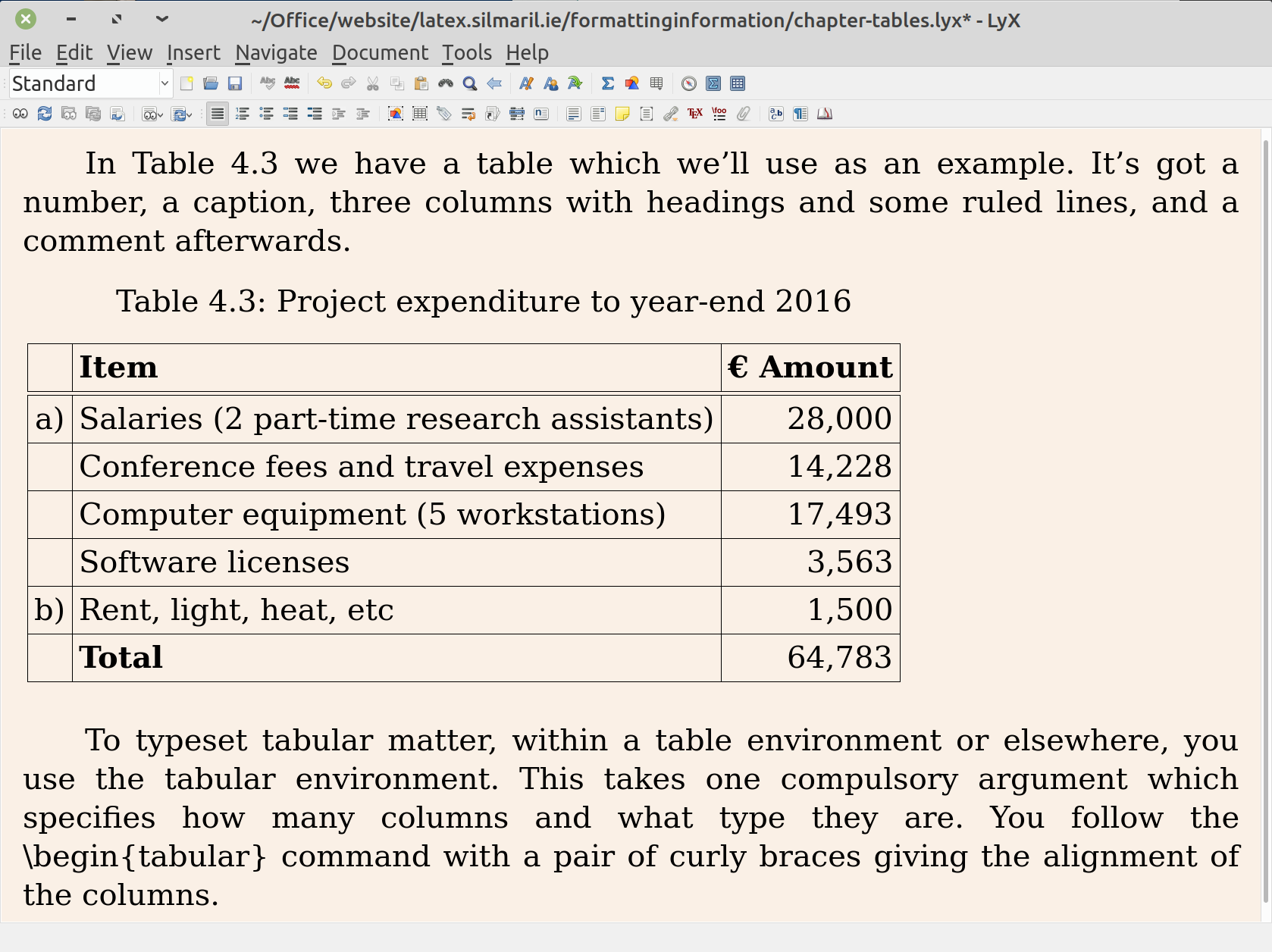

Figure 4.1: Table being edited in LYX’s tabular editor

In Figure 4.1 above and Table 4.3 above there is the table which we’ll use

as an example. It’s got a number, a caption, three columns

with headings and some ruled lines, and a comment

afterwards.

- The tabular environment

This takes one

compulsory argument which specifies how many columns

there will be, and what type they are.

You give one letter for each column using one of

l, c, and r for

a left-aligned, centered, or right-aligned column. The

number of letters MUST

be the same as the number of columns you are putting

in the table.

\begin{tabular}{clr}

...

\end{tabular}In the example in Table 4.3 above, the

tabular setting has three columns, the first one

centered, the second left-aligned, and the third one

right-aligned, so it is specified as

{clr}. The dcolumn package

provides a d column type for decimal

alignment, and there are others we shall come across

later.

Note

Each cell of these types (c,

l, r, d)

can hold only one line of data

in its cell. If you need

multi-line cells (like miniature paragraphs), see

§ 4.2.4 below

- Cell and row division

You can then type in each row, making sure each

cell’s data in the row is separated with an

& character, and each row ends with a

double backslash

(\\).

a)&Salaries (2 part-time research assistants)&28,000\\

You don’t need to add any extra spaces or do any

manual formatting, although you can if you want:

LATEX just uses the column specifications to know how

to format it.

If a cell has nothing to go in it, you just don’t

type anything, but the ampersand must still be

there:

&Total&64,783\\

- Column headings

These are often set in bold

type, as in the example (see ‘Cell

formatting’ below).

&\textbf{Item}&\textbf{\EUR\ Amount}\\[6pt]\hlineIn this case there is also some extra space (6pt,

see ‘Row spacing’ below) to make it look nicer,

and a horizontal line across

the table (see item ‘Table rules’ below).

The data for a row may be longer than the width

of the screen window in your editor, but it can take

up as many lines on the screen as needed; the end

of the row is always signalled by the double backslash,

so LATEX knows when it’s time for the next row.

- Cell formatting

Font changes can be done within a cell (bold,

italic, etc; we’ll come on to these later, see § 6.2.4 below) and these changes are

limited to the cell in which they occur: they do not

‘bleed’ across cells (in the

example, the column headings have each been made bold

separately).

- Row spacing

Additional vertical white-space

below a row (but above a rule)

can be specified by giving a dimension in [square

brackets] immediately after the double backslash which

ends the row (3pt in the case of the last row before

the totals in the example). A negative value will

decrease the spacing below that row.

If the line below a horizontal rule looks too

close, it can be optically spaced by adding a

strut at the start of the next

line (that is, after the

\hline). A

‘strut’ is hidden vertical rule

a little bit higher than the row-height; hidden

because its width is zero, making it invisible, as in

the example code. Use the \rule command

for this, with a width of 0pt and height

of 1.2em, just a fraction higher than the text,

which will force the rows apart by 0.2em.

\begin{table}

\caption{Project expenditure to year-end 20}

\label{ye2022exp}

\centering\smallskip

\begin{tabular}{clr}

&\textbf{Item}&\textbf{\EUR\ Amount}\\\hline\rule{0pt}{1.2em}

a)&Salaries (2 part-time research assistants)&28,000\\

&Conference fees and travel expenses&14,228\\

&Computer equipment (5 workstations)&17,493\\

&Software&3,562\\

b)&Rent, light, heat, etc.&1,500\\[3pt]\cline{2-3}

\rule{0pt}{1.2em}&Total&64,783\\

\end{tabular}

\par\medskip\footnotesize

The Institute also contributes to (a) and (b).

\end{table}- Table rules

A line across the whole table is done with the

\hline command after the

double-backslash which ends a row.

For a line which only covers some of the columns,

use the \cline command (in the same

place), with the column range to be ruled in curly

braces. If only one column needs a rule, it must still

be given as a range (eg in the example,

{3-3}).

Vertical rules (between columns) can be specified

in the column specifications with the vertical bar

character (|) before, after, or between

the l, c, r

letters. This character creates rules which extend the

whole height of a table: it is not necessary to repeat

them every row.

I have indented the code example given just to make the

elements of the table clearer to read: this is for editorial

convenience, and has no effect on the formatted result (see

Table 4.3 above). If you copy and paste this

into your example document, you will need to add the

marvosym package to your Preamble, which

will let you use the official CEC-conformant Euro symbol

command \EUR (€ as distinct from

€).

4.2.4 More complex tabular formatting

TEX’s original tabular environment was

designed for classical numerical grids, where each cell

contains a single value. If you need a cell to contain

multiline text, like a miniature paragraph, you can use the

column specification letter p (paragraph)

followed by a width in curly braces instead of an

l, c, or r. So

p{3.5cm} would mean a column 3.5cm wide, where

each cell can contain paragraph-style text, for example:

\begin{tabular}{cp{3.5cm}r}These p column specifications are

not multi-row (row-spanned) entries:

they are single cells which can contain multiple lines of

typesetting: the distinction is extremely important. These

paragraphic cells are typeset justified (two parallel

margins) and the baseline of the top line of text is aligned

with the baseline of neighbouring cells in the row.

The array package provides some

important enhancements which overcome the limitations of the

p cells:

- Vertical alignment

In addition to the p, whose vertical

alignment baseline is the the top line of text, the

array package provides the

m and b letters. These work

the same way as p (followed by a width in

curly braces), but their vertical alignment baseline

is the middle or bottom of the cell

respectively.

- Prefixes and suffixes

With the array package, any

column specification letter can be preceded by

>{} with some LATEX commands in the

curly braces. These commands are applied to every cell

in that column, so to make a p column

typeset ragged-right you would say, for example,

>{\raggedright}p{3.5cm} (or

\raggedleft, or

\centering).

Note that if you do this, the last column

specification MUST

include a prefix or suffix containing the

\arraybackslash command, to revert

the meaning of the double-backslash, which gets

redefined by horizontal formatting commands like

\raggedright, otherwise you will get

errors when the end-of-row double-backslash is not recognised.

There is a suffix format as well: you can follow a

column letter with <{} with code in

the curly braces (often used to turn off math mode

started in a prefix).

The colortbl package lets you colour

rows, columns, and cells; and the dcolumn

package mentioned above provides decimal-aligned column specifications for

scientific or financial tabulations. Multi-column

(column-spanning) is built into LATEX tables with the

\multicolumn command; but for multi-row

(row-spanning) cells you need to add the

multirow package. Multi-page and rotated

(landscape format) tables can be done with the

longtable, rotating,

and landscape packages.

The LATEX table model is very different from the

HTML auto-adjusting model used in web

pages; it’s closer to the Continuous

Acquisition and Life-cycle Support (CALS) table model used

in technical documentation formats like DocBook. However,

auto-adjusting column widths are possible with the

tabularx and tabulary

packages, offering different approaches to dynamic table

formatting.

You do not need to format the tabular data in your

editor: LATEX formatting will typeset the

table using the column specifications you provided. You can

therefore arrange the layout of the data in your file for your

own convenience: you can

give the cell values all on one line, or split over many

lines: it makes no difference so long as the cells are separated

with the & and the rows are ended with the

double-backslash.

As mentioned earlier, some editors have a grid-like

array editor for entering tabular data. Takaaki Ota provides an

excellent tables-mode for

Emacs which uses a

spreadsheet-like interface and can generate LATEX table

source code (see Figure 4.2 below).

Figure 4.2: Tables mode for

Emacs

4.2.5 More on tabular spacing

Extra space, called a ‘shoulder’,

is automatically added on both sides of all columns by

default. The initial value is 6pt, so you get that amount

left and right of the tabulation; because it is added left

and right of every cell, the space between columns is

therefore 12pt by default. This can be adjusted by changing

the value of the \tabcolsep

dimension before you begin the tabular

environment.

\setlength{\tabcolsep}{3pt}The shoulder can be omitted in specific locations by adding

the code @{} in the appropriate place[s] in the

column specification argument. For

example to omit it at the left-hand and right-hand sides of

a tabular setting, put it at the start and end of the column

specifications (putting it between two column specifications

will remove all space between those columns).

\begin{tabular}{@{}clr@{}}You can also use @{} to insert different

spacing between columns (or at the right-hand and left-hand

sides) by enclosing a spacing value; for example,

@{\hspace{2cm}} could be used to force a 2cm

space between two columns.

To change the row-spacing in a tabular setting, you can

redefine the \arraystretch command (using

\renewcommand because it’s

defined as a command, not a length). The value of

\arraystretch is actually a multiplier, preset

to 1, so

\renewcommand{\arraystretch}{1.5} would

set the baselines of your tabular setting one and a half

times further apart than normal.

Exercise 4.3 — Calculate vertical spacing in a tabular environment

Assume that you are making a table in the default size

of 10pt type on a 12pt baseline. You want a 14pt baseline,

so what value would you set \arraystretch

to?

It is conventional to centre the tabular setting within

a Table, using the center environment (note

US spelling) or the \centering command (as

in the example) — the default is flush left — but

this is an æsthetic decision. Your journal or

publisher may insist

instead that all tabular material is set flush left or flush

right (not the individual columns; the whole tabular setting

inside the table).

If there is no data for a cell, just don’t type

anything — but you still need the &

separating it from the next column’s data. The astute

reader will already have deduced that for a table of

n columns, there must always be

n-1 ampersands in each row. The exception to

this is when the \multicolumn command is

used to create cells which span multiple columns, when the

ampersands of the spanned columns are omitted. The

\multicolumn command takes three arguments:

the number of columns to span; the format for the

resulting wide column; and the contents. So to span a

centred heading across three columns you would write

\multicolumn{3}{c}{The new heading}.

The \multicolumn command can also be used to

replace a single column if you need to vary some

prefixing or suffixing or alignment specified in the column

specification. For example if you have a right-aligned column

(eg numbers) but you want one of the cells to be some text

centered, you could

write \multicolumn{1}{c}{no data}. In this case, of

course, you keep all the ampersands, because you are not actually

spanning columns.

4.2.6 Techniques for alignment

As mentioned earlier, it’s perfectly possible to use the

tabular environment to typeset any grid of

material — it doesn’t have to be inside a formal

table. There are also other ways to align material without

using a tabular format.

4.2.6.1 Using tabular alignment outside a table

By default, LATEX typesets tabular

environments inline to the

surrounding text. That is, the tabular

environment acts like a single character within the

paragraph. This also means if you want an alignment

displayed by itself, not as part of a formal table, you

can put it between paragraphs (with a blank line or

\par before and after) so it gets

typeset separately; or put it inside a positioning

environment like center,

flushright, or

flushleft.

One side-effect of this is that small and intricately

constructed micro-tabulations can be used to good effect

when creating special effects like logos, as they they get

treated like a character and can be typeset

anywhere.

Tabular setting can be used wherever you need to align

material side by side, such as in designing letterheads,

where you may want your company logo and address on one

side and some other information on the other side to line

up with each other. One common way to implement

‘spring margins’ like this is to create two columns of whatever

fraction of the page width you need (but adding to 1, of

course), and removing for the extra space that would

otherwise be added automatically between columns and at

the edges:

\begin{tabular}{

@{}

>{\raggedright}p{.75\textwidth}

@{}

>{\raggedleft\arraybackslash}p{.25\textwidth}

@{}}

left-hand material

&

right-hand material\\

\end{tabular}As mentioned earlier, the @{} suppresses

the inter-column gap (or the shoulder left or right) so

that the total width available will be the full text width

of the page.

Exercise 4.4 — Create a tabulation

Create one of the following in your document:

a formal Table with a caption showing the number

of people in your class broken down by age and

sex;

an informal tabulation showing the price for

three products;

the logo ![\setlength{\fboxsep}{3pt}\setlength{\fboxrule}{.4pt}\fbox{\begin{tabular}{@{}c@{}}\bfseries Y E A R\\[-2pt] \bfseries 2 0 0 0\vrule depth.5ex width0pt\end{tabular}}](images/y2klogo-crop.png) (hint:

§ 4.6.2 below)

(hint:

§ 4.6.2 below)

4.2.6.2 Alignment in general

Within the two-dimensional plane of conventional

typesetting, there are two sets of axes to which the

elements of the document should align: horizontal and

vertical.

The vertical axes are the left and right edges of

the paper, the left and right margins of the text

area, indentation, any internal temporary left and

right margins (as for lists, block quotation,

displayed mathematics, the left and right edges of

illustrations, etc), and any internal column

boundaries of a tabular

environment.

The horizontal axes are the top and bottom edges

of the paper, the top and bottom margins of the text

area, the space for running headers and footers, the

top and bottom edges of all

‘pool’ items (see the start of

this chapter), the baseline of the text, and any

internal row boundaries of a tabular

environment.

Warning

If someone says they want something

‘aligned’, you need to ask ‘aligned

to what, exactly’? It’s

not always obvious, and in unusual cases it’s not always

easy to find out how to calculate or access an axis

without careful study of the internal programming of a

class or package.

By default, LATEX starts each line up against the

left-hand margin: if indentation is used, then the first

lines of paragraphs will be indented,

except for the first paragraph after

a heading.

Depending on the language you select in the

babel or

polyglossia packages, the first

lines of first paragraphs after a heading may

not be indented (for example in

French typesetting).

In right-to-left languages, the alignment is

reversed, and lines start up against the right-hand

margin, and (see below) end against the left-hand

margin.

The typeset line extends to the right-hand margin, and

the process of justification ensures that all line-ends,

apart from the last in a paragraph, align with this

margin. The exception is when a raggedright

or raggedleft or centering

alignment has been specified.

Alignment to the four paper edges is extremely rare

except in magazines and specialist formats like corporate

reports or white papers, where images may be positioned to

the edge[s] of the paper, and are said to

‘bleed’ off the sheet. It is of

course possible in LATEX but it is well outside the

scope of this introductory text for beginners.

4.2.6.3 Alignment within pool items

While typesetting a paragraph, LATEX has no way to

become aware of whereabouts a particular word or letter is

being placed, for two reasons:

The justification of the paragraph does not start

until after the whole paragraph has been typeset; only

then does TEX start testing for line-end

breakpoints, assigning them penalties, and inserting

the variable spacing between words. This process is

synchronous with the typesetting of the paragraph, and

the next paragraph will not be started until

justification of the one just ended is

complete.

The positioning of the paragraph vertically on the

page does not start until well after at least a whole

page’s worth of material has been typeset and

justified, and the ‘galley’ of

accumulated material comes close to filling up. At

this point, TEX pauses typesetting of the next page

(which it has already started), finds the optimum

place to break the page, sends the completed page to

the output, resets the accumulator to the remaining

material, and then resumes typesetting. This process

of page-building is therefore

asynchronous with the process of

typesetting, and the point at which access to

already-typeset material ceases to be possible is not

predictable in meaningful terms.

This means that doing things with stuff that has

already been dealt with really isn’t possible, and

requests for it have to be respectfully declined. Anything

you need to do with an item, whether it’s a letter or a

word or a paragraph, like applying a font change or

putting it in a box, for example, needs to be done

in situ,

before it disappears down TEX’s

throat.

While there are packages for dealing with

completed paragraphs, such as

reledpar for typesetting synchronised

parallel-page (eg dual-language) editions, access to the

inside of the paragraphs is not possible at this stage. It

is, however, possible to typeset

material into a box, and then do things with it, including

emptying it all back out again, in a limited manner. This

makes it possible to see how much space a particular item

is going to occupy, and then decide whether or not to

treat it in a certain way. Standard LATEX does this when

deciding if a table or figure caption is narrow enough to

fit centered on one line, or if it needs to set it

full-out.

Packages which provide their own alignment options,

such as enumitem for finer control of

lists, usually specify in the documentation how to

manipulate the shape and appearance of their environments.

A substantial amount of this is about how to align one

atomic value, such as a heading or title, with another

one, such as the word which comes after it. In the case of

the lettrine for dropped initial

capitals, it’s about how to adjust the capital (up, down,

right, left) with respect to the indented rectangle into

which it is to fit. In the case of the

colortbl package for coloured rows and

columns and cells in tables, it includes details of how to

get the coloured block microadjusted.

4.2.6.4 Alignment to margins

The geometry package has extensive

features for specifying the paper size, page size, margin

sizes (left and right, if you are typesetting for

double-sided work), marginal gaps, the head and foot

settings for headers, footers, footnotes, and the gaps

between them.

The description of line-alignment in the preceding

section holds true for all text typeset inside further

environments, for example in an abstract or

a quotation, and within all lists, as well

as the

p/m/b

column formats within a tabular setting. So

long as you remain aware of the possible effect of

unscoped formatting commands on lower-level nested

environments, you can nest one environment inside another

to an unspecified depth, and the rules of alignment will

continue to be applied as much as possible. However, as

with HTML and CSS,

it is possible to overuse or abuse nesting, as it makes

the code obscure.

Because the nesting of environments implies

encapsulation, access to the alignment points (eg margins)

of an outer environment is often not possible inside a

deeper-nested environment. The TEX language model allows

for the inheritance of settings defined at a higher level,

but where these values are implemented as part of the code

creating both the current environment

and a higher one (eg lists inside

lists), they will occupy the same space, and only the

local value will be accessible. In such cases, any values

needed would have to be saved in a variable accessible to

the lower-level environment. In 30+ years of using LATEX

I have only ever needed to do this once.

4.2.6.5 Grids

Outside the tabular environment,

LATEX does not use a grid system.

Its origins in mathematics mean that because displayed

equations can occupy non-integer numbers of

‘lines’ (compared with text, which

always occupies a whole number of lines), it was judged

better for quality to allow flexible space

between headings and paragraphs. Over

the depth of a whole page, this minute amount of

flexibility usually absorbs the fractional part of a

line-height due to overspill in formulas (part of which

‘rubberisation’ led Leslie Lamport to choose LATEX as the name for his set

of macros).

There is a grid package available

which enables grid setting in double-column documents, but

overall there is no easy way to

‘snap’ pool elements to arbitrarily

distanced gridlines. The flexibility of \parskip and the dozen or more

other ‘skips’ (flexible lengths) in

the LATEX source (latex.ltx) could

be removed, and display mathematics set in boxes of an

integer number of \baselineskips, and

special environments could be written to anchor themselves

to a specific corner, but in general, the model of

flexibility has proved itself over nearly 40 years, and

requirements for grid models should be transferred to the

NTS in the care of

TUG and the LATEX development

specialists.

![\setlength{\fboxsep}{3pt}\setlength{\fboxrule}{.4pt}\fbox{\begin{tabular}{@{}c@{}}\bfseries Y E A R\\[-2pt] \bfseries 2 0 0 0\vrule depth.5ex width0pt\end{tabular}}](images/y2klogo-crop.png)