As we well see later, a similar method is also used to

cite documents for a bibliography or list of references, and

there are packages to sort and format these in the correct

style for different journals or publishers.

5.3.1 Cross-references

You label the place in your document you want to refer

to by adding the command

\label followed by a short name you make

up, in curly braces: exactly as we did for labelling

Figures and Tables in § 4.2.2 above.

\section{New Research}

\label{newstuff}You can then refer to this place from anywhere in the

same document with the command \ref

followed by the name you used, eg

Note the use of the unbreakable space

(~) between the \ref and

the word before it. This prints a space but prevents the

line ever breaking at that point, should it fall close

to the end of a line when being typeset.

The \S command can be used if you

want the section sign § instead of the word

‘section’ (there is also a

\P command that produces the paragraph

sign or pilcrow ¶).

Labels MUST be unique

(that is, each value MUST

occur only once as a label within a

single document), but you can have as many references to

them as you like. If you are familiar with

HTML, this is the same concept as the

internal linking mechanism using #

labels (or IDs in

XHTML or HTML5).

- Labels in normal text

If the label is in normal text, as above, the

reference will give the current

chapter/section/subsection/appendix number (depending on the

current document class).

- Labels in Tables or Figures

If the label is inside a Table or Figure, the

reference provides the Table number or Figure number

prefixed by the chapter number (remember that in

Tables and Figures the \label

command MUST come

after the

\caption command).

The \ref command does not

produce the word ‘Figure’ or

‘Table’ for you: you have to

type it yourself, or use the

varioref package which automates

it.

- Labels in lists

A label in an item in an enumerated list will

provide the item number. In other lists its value is

null or undefined.

- Labels elsewhere

If there is no apparent countable structure at the

point in the document where you put the label (in a

bulleted list, for example), the reference will be

null or undefined.

The command \pageref followed by any

of your label values will provide the page number where the

label occurred, instead of the reference number, regardless

of the document structure. This makes it possible to refer

to something by page number as well as by its

\ref number, which is useful in

very long documents like this one

(varioref automates this too).

Process twice!

LATEX records the label values each time the

document is processed, so the updated values will get used

the next time the document is

processed. You therefore need to process the document one

extra time before final printing or viewing, if you have

changed or added references, to make sure the values are

correctly resolved. Most LATEX editors handle this

automatically by typesetting the document twice when

needed.

Unresolved references are printed as two question marks,

and they also cause a warning message at the end of the log

file. There’s never any harm in having

\labels you don’t refer to, but using

\ref when you don’t have a matching

\label is an error, as is defining two

labels with the same value.

5.3.2 Bibliographic references

The mechanism used for references to reading lists and

bibliographies is very similar to that used for normal

cross-references. Instead of using \ref

you use \cite or one of the variants

explained in § 5.3.2.3 below; and instead of

\label, you attach a label value to each

of the reference entries for the books, articles, reports,

etc that you want to cite. You keep these reference entries

in a bibliographic reference database

that uses the BIBTEX data format (see § 5.3.2.2 below).

This does away with the time needed to maintain and

format references each time you cite them, and dramatically

improves accuracy. It means you only ever have to enter the

bibliographic details of your references once, and you can

then cite them in any document you write, and the ones you

cite will get formatted automatically to the style you

specify for the document (eg Harvard, Oxford, Institute of Electrical and Electronics

Engineers (IEEE), Vancouver, Modern Language Association (MLA),

American Psychological

Association (APA), etc).

5.3.2.1 Choosing between BIBTEX and

biblatex

LATEX has two systems for doing citations and

references, BIBTEX (old) and biblatex

(new): both of them use the same bibliographic file

format, also called BIBTEX, for storing and managing

your references. Both support the four common ways of

indicating a citation: author-year, numeric, abbreviated

alphabetic, and footnoted, plus a wide range of

others.

- BIBTEX

the older BIBTEX has been in use for many

decades and is still specified in some publishers’

document classes, especially for journal articles

and books, and particularly those which have not

been updated for a long time. While it will continue

to work, it has several major drawbacks:

it doesn’t handle non-ASCII characters

easily, so accents and non-Latin words or

languages are a problem;

the same applies to the sort-and-extract

program it uses (also called

bibtex)

the style format files

(.bst files) are written in

BIBTEX’s own rather strange, unique, and

largely undocumented language, making it

extremely difficult to modify them or write new

ones;

many of the style format files are now very

old and out of date;

the range of data fields in references is

limited and also out of date.

- biblatex

the newer biblatex system is

now a well-established LATEX package to replace

almost all of old BIBTEX. The main advantages

are:

it uses the same .bib

files as for old BIBTEX, but adds many

new document types and data field names.

it works with Unicode, so

non-ASCII, non-Latin, and other writing systems

are handled natively when using LuaLATEX.

there is a new sort-and-extract program

(biber) to replace

bibtex, which also

handles Unicode natively.

the style format files are written entirely

in LATEX syntax, and are under active

development, so updating or writing layout

formats it is much easier than with

BIBTEX.

it supports the four popular citation

formats listed above natively, without the need

for additional packages.

The only current drawback is that there are

still a few uncommon and less-used reference formats

that are still only supported in BIBTEX and not

yet available in biblatex. If you

are required to use one of these, you are going to

be stuck with BIBTEX (unless you’d like to write a

new biblatex add-on to handle

it).

The biblatex package with the

biber program is therefore

recommended, especially with LuaLATEX. From here on, I

shall be using only biblatex.

5.3.2.2 The BIBTEX file format

The same file format for BIBTEX files is used for

both BIBTEX and biblatex, regardless

of whether you use biber or

bibtex, so if you have existing

BIBTEX files, they will continue to work, but it’s a

good idea to update old files with some of the more

accurate field names provided by

biblatex.

The file format is specified in the original

BIBTEX documentation (look on your system for

the file btxdoc.pdf). The

biblatex package and its updated style

formats provide many more fields and document types than

we can describe here.

Each BIBTEX entry starts with an @ sign

and the type of document (eg @article, @book, etc), followed by the

whole entry in a single set of curly braces. The first

value MUST be a unique

BIBTEX key (label) that you make up, which you will use

to cite the reference with; followed by a comma:

@book{fg, ... }Then comes each field (in any order), using the

format:

fieldname = {value},There MUST be a comma

after each line of an entry except the last

line (see the rules below):

@book{fg,

title = {{An Innkeeper’s Diary}},

author = {John Fothergill},

edition = 3,

publisher = {Penguin},

year = 1929,

address = {London}

}Some TEX-sensitive editors have a BIBTEX mode

which understands these entries and provides menus,

templates, and syntax colouring for writing them. The

rules are:

There MUST be a

comma after each line of an entry except the

last line;

There MUST NOT be a

comma after the last field in the entry;

Some styles recapitalise the title when they

format: to prevent this, enclose the title in double

curly braces as in the example;

You MUST use extra

curly braces to enclose multi-word surnames, otherwise

only the last will be used in the sort, and the others

will be assumed to be forenames, for example the

British explorer can be sorted under T as

author = {Ranulph {Twisleton Wykeham Fiennes}},Multiple authors

MUST go in a single

author field, separated by the literal

word and (see example below)

Values which are purely numeric (eg year and month) may

omit the curly braces;

Months and editions

MUST be numbers (and

may therefore omit the curly braces);

DO NOT include ordinal

indicators like th or

st;

Fields MAY occur in

any order but the format

MUST otherwise be

strictly observed;

Fields which are not used do not have to be

included (so if your editor automatically inserts them

as blank or prefixed by OPT [optional],

you MAY safely delete

them as unused lines)

There is a required minimum set of fields for each of

a dozen or so types of document: book, article (in a

journal), article (in a collection), chapter (in a book),

thesis, report, conference paper (in a Proceedings), etc,

exactly as with all other reference management systems.

These are all (entry types and entry fields) listed in

detail in the biblatex documentation

(Lehman, Kime, Boruvka & Wright, 2015, sections 2.1 & 2.2 p.8).

Here’s another example, this time for a book on how to

write mathematics — note the multiple authors separated by

and. Long entries can spread over several

lines: the extra spaces and line-breaks are ignored, so

long as the value ends with the matching curly brace (and

comma, if needed).

@book{mathwrite,

author = {Donald E Knuth and Tracey

Larrabee and Paul M Roberts},

title = {{Mathematical Writing}},

publisher = {Mathematical Association of America},

address = {Washington, DC},

series = {MAA Notes 14},

isbn = {0-88385-063-X},

year = 1989

}Every reference in your reference database

MUST have a unique key

value (label or ID): you can make this up, just like you

do with normal cross-references, but some bibliographic

software automatically assigns a value, usually based on

an abbreviation of the author and year. These keys are for

your convenience in referencing: in

normal circumstances your readers will not see them. You

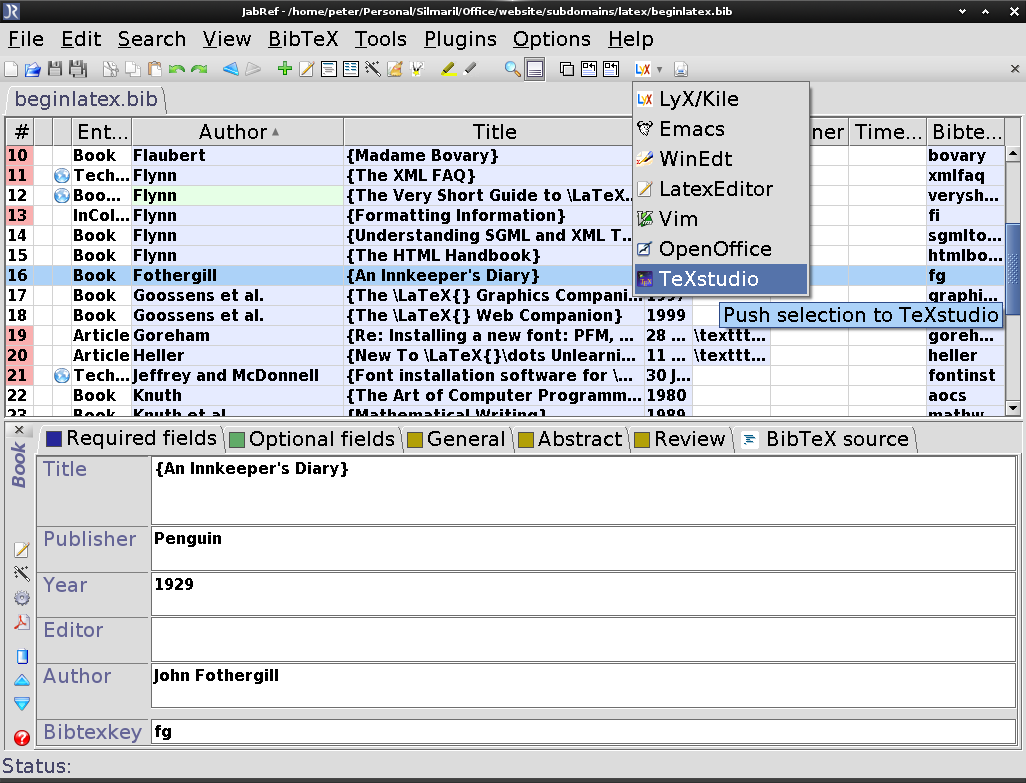

can see these labels in the right-hand-most column and at

the bottom of the screenshot in Figure 5.1 below, and in the examples above. You use

these labels in your documents when you cite your

references (see § 5.3.2.3 below).

There are many built-in options to the

biblatex package for adjusting the

citation and reference formats, only a few of which are

covered here. Read the package documentation for details:

it is possible to construct your own style simply by

adjusting the settings, with no programming required

(unlike the older BIBTEX styles, which are written in a

programming language used nowhere else).

Many users keep

their BIBTEX files in the same directory as their

document[s], but it is also possible to tell LATEX and

BIBTEX that they are in a different directory. This is a

directory specified by the $BIBINPUTS shell or environment

variable set up at installation time. On Unix &

GNU/Linux systems (including Apple

Macintosh OS X), and in TEX Live for Windows,

this is your TEX installation’s

texmf/bibtex/bib directory — the

same one that old-style BIBTEX .bst

style files are kept in — but to avoid permission

conflicts you should use your Personal TEX Directory and

create a subdirectory of the same name in there for your

own .bib files. MiKTEX also uses

the same $BIBINPUTS

variable, but it is not set on installation: you need to

set it using the Windows Systems Settings (see for example

https://www.computerhope.com/issues/ch000549.htm).

5.3.2.3 Citation commands

The basic command is \cite, followed

by the label of the entry in curly braces. You can cite

several entries in one command: separate the labels with

commas.

\cite{fg}

\cite{bull,davy,heller}For documents with many citations, use the

Cite button or menu item in your

bibliographic reference manager, which will insert the

relevant command for you (you can see it activated for the

TEXStudio

editor in Figure 5.1 below).

How the citation appears is governed by two

things:

the reference format (style) you specify in the

options to the biblatex package

(see § 5.3.2.4 below)

the type of citation command you use:

\cite, \textcite,

\parencite,

\autocite,

\footcite, etc, as shown

below.

There are four built-in formats in

biblatex:

- 1.

authoryear

There are two basic types of author–year

citation:

- a.

author as text, year in parentheses

used in phrases or sentences where the

name of the author is part of the sentence,

and the year is only there to identify what is

being cited; this command is

\textcite{fg}

...as has clearly been

shown by Fothergill (1929).

This is sometimes called

‘author-as-noun’

citation.

- b.

whole citation in parentheses

used where the phrase or sentence is

already complete, and the citation is being

added in support: this command is

\parencite{fg}

...as others have

already clearly shown (Fothergill, 1929).

The references at the end of the document are

sorted into surname order of the first author, and

by year after that.

- 2.

numeric

This format is popular in some scientific

disciplines where \cite produces

just a number in square brackets, eg [42]. The

references at the end of the document are usually

numbered either in order of

citation or in order of first

surname;

- 3.

alphabetic

This format is also popular in some scientific

disciplines and \cite produces a

three- or four-letter abbreviation of the author’s

name and two digits of the year, all in square

brackets, eg [Fot29]. The references at the end of

the document are sorted using abbreviated key value

as their label. This format is also called

‘abbreviated’.

- 4.

footnoted

Footnoted citations are common in History and

some other Humanities disciplines, so much so that

scholars in these fields actually call their

references

‘footnotes’. The command \footcite

produces a superscript number like an ordinary

footnote, and a short reference at the foot of the

page. It is only relevant when using author-year

styles (in numeric style it would just produce the

reference number at the foot of the page, which

would be misleading because it would be different to

the actual footnote number!). The references at the

end of the document are given in full, and are

usually sorted alphabetically by first

surname.

There is also a \fullcite command

which produces a fully-fledged reference

within the paragraph, so

\fullcite{fi2002} produces

Flynn, Peter (2002) ‘Formatting Information’. In ‘TUGboat’, 23:2, pp. 115-250, URI http://www.ctan.org/tex-archive/info/beginlatex/..

To direct your reader to a specific page or chapter in

your reference, you can add a prefix and/or a suffix as

optional arguments in square brackets before the

label.

...as shown by \textcite[p 12]{mathwrite}.A prefix gets printed at the start of the citation and

the suffix gets printed at the end, but all still within

the parentheses, if any. As they are both optional

arguments, and as suffixes are far more common than

prefixes, when only one optional argument is given, it is

assumed to be the suffix. The example above therefore

produces:

...as shown by Knuth, Larrabee & Roberts (1989, p 12).

There are many variant forms of the citation commands,

either for specific styles like Chicago, Vancouver,

Harvard, IEEE, APA, MLA, etc; or for grammatical

modifications like capitalising name prefixes, omitting

the comma between name and year, or adding multiple notes;

or for extracting specific fields from an entry (eg

\titlecite). If you have requirements

not met by the formats described here, you can find them

in the documentation for the biblatex

package.

Modern Language Association (MLA) citation is a

special case, as it omits the year and instead

REQUIRES the location of

the citation within the document (eg the chapter, section,

page, or line). It may include the title, if there would

otherwise be ambiguity. The biblatex

format for MLA citation handles the context-dependent

formatting with the command

\autocite.

Table 5.1: Built-in biblatex style commands

and formats

| Style | Command | Result |

| authoryear | \parencite{fg} | (Fothergill, 1929) |

| authoryear | \textcite{fg} | Fothergill (1929) |

| authoryear | \footcite{fg} | ¹ |

| numeric | \cite{fg} | [42] |

| alphabetic | \cite{fg} | [Fot29] |

| authoryear | \cite{fg} | Fothergill 1929 |

¹ Fothergill 1929.

Figure 5.1: JabRef displaying a file of references, ready to

insert a citation of Fothergill’s book into a LATEX

document being edited with TEXStudio

Your reference management software will have a display

something like Figure 5.1 above (details vary

between systems, but they all do roughly the same job in

roughly the same way), showing all your references with

the data in the usual fields (title, author, date,

etc).

Your database, which contains all your bibliographic

data, MUST be saved or

exported as a BIBTEX format (.bib)

file from your reference management software

(JabRef uses this format

automatically), It looks like the examples in

§ 5.3.2.2 above. Your .bib

file works with both biblatex

and BIBTEX, but

biblatex provides more field types and

document types so that your references can be formatted

more accurately.

If your bibliographic management software doesn’t save

BIBTEX format direct, save your data in

RIS format, then import the

.ris file into

JabRef and save it as a

.bib file from there.

Cheatsheet

Clea F Rees has written an

excellent cheatsheet with virtually everything on it

that you need for quick reference to using

biblatex. This is downloadable as the

package biblatex-cheatsheet from

CTAN.

Exercise 5.1 — Using biblatex

Use your bibliographic database program (eg

JabRef or similar) to

create a file with your references in it (see

§ 5.3.2.2 above). You could type them by

hand if you want, but it's faster and more reliable

to use a database.

Make sure each entry has a unique

short keyname (bibtexkey) to

make citations with

Save the file with a name ending in

.bib (eg

myrefs.bib) in the same folder

as your LATEX document

Add these two lines to the Preamble of your LATEX

document:

\usepackage[backend=biber,style=authoryear]{biblatex}

\addbibresource{myrefs.bib}In the body of your document, where you want to

cite a work, use

\parencite{keyname} or

\textcite{keyname} as appropriate

(see Table 5.1 above for

examples)

Towards the end of your document, add the

command \printbibliography at the

point where you want the bibliography printed

Typeset the document: that is, run

lualatex, then

biber, and then

lualatex again (most

editors automate this for you)

When you’ve got the citations and references

working, read the BIBTEX

documentation for all the extra things you can do

5.3.2.4 Setting up biblatex with

biber

For more complex citation requirements, you may need

to set up your document with the following

packages:

the babel or

polyglossia package with

appropriate languages, even if you are only

using one language. The default language

is American English, so there are commands to map this

to other language variants (the example below shows

this for British English)

the csquotes package, which

automates the use of quotation marks around titles or

not, depending on the type of reference;

the biblatex package itself,

specifying the biber

program and the style of references you want, either

numeric, alphabetic, or

authoryear; or a publisher’s style; and

any options for handling links like DOIs, URIs, and

ISBNs;

the language mapping command, if needed (see the

documentation for the style you have chosen to find

out if you need this)

finally, the name of your BIBTEX file[s] (see

the sidebar ‘Bibliographic reference databases’ above) with one or more

\addbibresource commands.

\usepackage[frenchb,german,british]{babel}

\usepackage{csquotes}

\usepackage[backend=biber,doi=true,isbn=true,

url=true,style=apa]{biblatex}

\DeclareLanguageMapping{british}{british-apa}

\addbibresource{myrefs.bib}At the end of your document you can then add the

command \printbibliography (or elsewhere

that you want the full list

of references you have cited to be output). See

§ 5.3.2.5 below for details of how LATEX

produces the references.

Versions of biber and

biblatex

One critically important point to note is that

biblatex and

biber are step-versioned;

that is, each version of the biblatex

package only works with a specific version of the

biber program. There is a

table of these dependencies in the

biblatex documentation PDF. If you

manually update biblatex for some

reason (perhaps to make use of a new feature), you

MUST also update your

copy of biber to the correct

version, and vice versa,

otherwise you will not be able to produce a

bibliography.

5.3.2.5 Producing the references

Because of the record→extract→format process

(the same as used for cross-references), you will get a

warning message about ‘unresolved

references’ the first time you process your

document after adding a new citation for a previously

uncited work. LATEX inserts the label of the reference

in bold as a marker or placeholder until you run

biber and re-typeset the

document. This is why most editors have a

Build function to do the job for

you.

This function should therefore handle the business of

running biber and

re-running LATEXfor you. If not, here’s how to do it

manually in a Command window: you run LATEXthen run

biber to extract and sort the

details from the BIBTEX file, and then

run LATEXagain:

lualatex myreport

biber myreport

lualatex myreport

In practice, authors tend to retypeset their documents

from time to time during writing anyway, so they can keep

an eye on the typographic progress of the document. So

long as you remember to click the

Build or equivalent button after

adding a new \cite command, all

subsequent runs of LATEX will incrementally

incorporate all references without you having to worry

about it.

If you work from the command line, the

latexmk script automates this,

running bibtex or

biber and re-running LATEX

again when needed.