The methods vary from wordprocessors or plugins with a

menu entry for , to a

custom XSLT script for a bespoke

solution.

8.1.2 Bulk conversion

Converting large numbers of related documents using most

of the non-graphical (command-line) utilities is often

straightforward using a shell script in (eg)

bash or

Powershell. At the simplest level

it can just be a few lines like

for f in *.docx; do

pandoc -f docx -t latex $f ${f/docx/tex};

doneHowever, if you have large numbers of obsolete Word

.doc files (too many to open and save

as .docx), you can try to use a

specialist conversion tool like EBT’s

DynaTag (supposedly still

available from Enigma, if you can persuade them they have a

copy to sell you; or you may still be able to get it from

Red Bridge

Interactive in Providence, RI). It’s old and

expensive and they don’t advertise it, but for the

Graphical User Interface (GUI)-driven bulk conversion of

consistently-marked Word

(.doc, not

.docx) files into usable XML it beats

everything else hands down. But whatever system you use, the

Word files

MUST be consistent, though,

and MUST use Named Styles

from a stylesheet (template), otherwise no system on earth

is going to be able to guess what they mean.

There is of course an external way, suitable for large

volumes only: send it off to the Pacific Rim to be scanned,

retyped, or hand-edited into XML or LATEX. There are

hundreds of companies from India to Polynesia who do this at

high speed and low cost with very high accuracy. It sounds

crazy when/if document is already in electronic format, but

it’s a good example of the problem of low quality of

wordprocessor markup that this solution exists at

all.

8.1.3 Getting LATEX out of XML

You will have noticed that most of the solutions lead to

one place: XML. As explained above and

elsewhere, this format is the only one so far devised

capable of storing sufficient information in

machine-processable, publicly-accessible form to enable your

document to be recreated in multiple output formats. Once

your document is in XML, there is a large

range of software available to turn it into other formats,

including LATEX. Processors in any of the common

XML processing languages like

XSLT or

Omnimark can easily be written to

output LATEX, and this approach is extremely

common.

Much of this would be simplified if wordprocessors

supported native, arbitrary

XML/XSLT as a standard

feature, because LATEX output would become much simpler to

produce, but this seems unlikely.

However, since the early 2000s the internal format for

both OpenOffice (now

Libre Office) and

Word is now XML. Both

.docx and .odf

files are actually Zip files containing the XML document

together with stylesheets, images, and other ancillary

files. This means that for a robust transformation into

LATEX, you just need to write an XSLT stylesheet to do the

job — non-trivial, as the XML formats used are extremely

complex, but certainly possible.

Assuming you can get your document out of its

wordprocessor format into XML by some

method, here is a very brief example of how to turn it into

LATEX.

You can of course buy any fully-fledged commercial

XML editor with XSLT

support, and run transformations within it. However, this is

beyond the reach of many individual users, although

oXygen is available at a

discounted price to academic sites.

To do the job unaided you need to install three pieces

of software: Java,

Saxon

or another XSLT processor, and the

DocBook

5.0 DTD (links are correct at the time of writing). None of

these has a graphical interface: they are run from the

command-line.

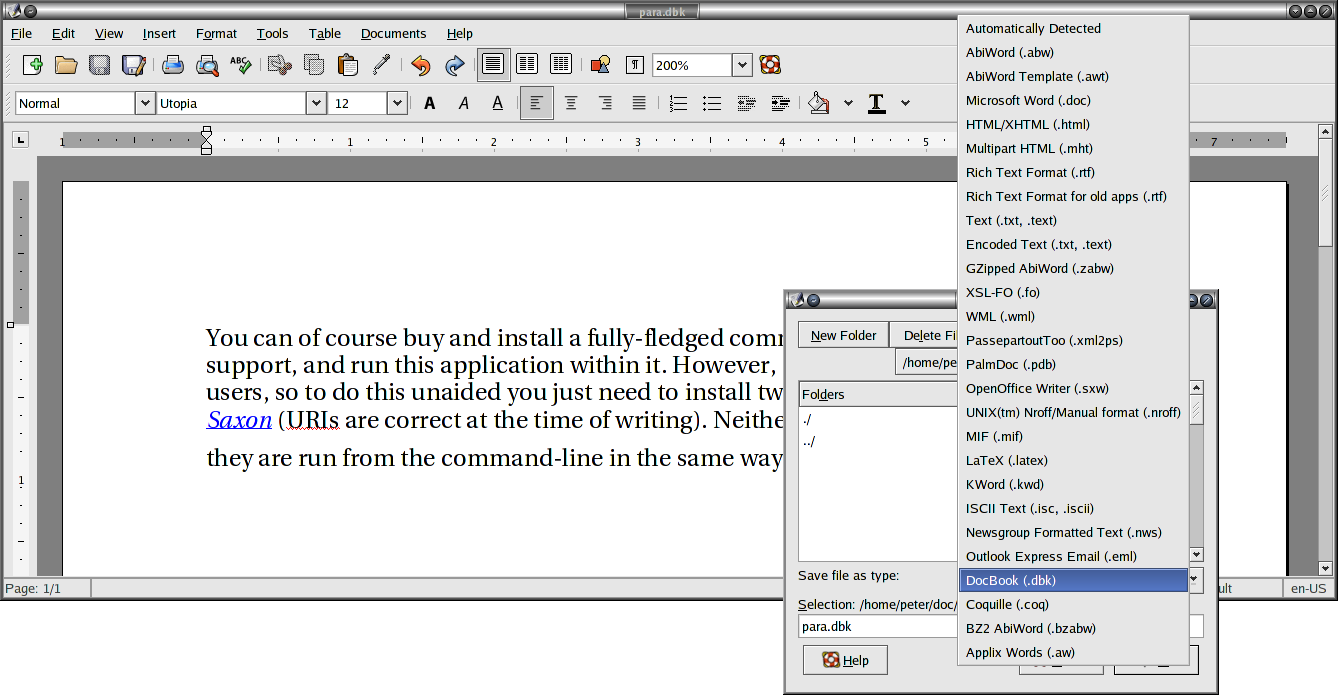

As an example, let’s take the a sample paragraph, as

typed or imported into AbiWord

(see Figure 8.3 below). This is stored as a single

paragraph with highlighting on the product names (italics),

and the names are also links to their Internet sources, just

as they are in this document. This is a convenient way to

store two pieces of information in the same place.

Figure 8.3: Sample paragraph in

AbiWord being converted to

XML

AbiWord can export in DocBook

format, which is an XML vocabulary for

describing technical (computer) documents — it’s what I

use for this book. AbiWord can

also export LATEX, but we’re going to make our own

version, working from the XML (Brownie

points for the reader who can guess why I’m not just

accepting the LATEX conversion output).

Although AbiWord’s default is

to output an XML book

document type, we’ll convert it to a LATEX article

document class. In this example I’ve changed the linebreaks

to keep it within the bounds of the page size of the

PDF edition:

<!DOCTYPE book PUBLIC "-//OASIS//DTD DocBook XML V4.2//EN"

"http://www.oasis-open.org/docbook/xml/4.2/docbookx.dtd">

<book>

<!-- ================================================== -->

<!-- This DocBook file was created by AbiWord. -->

<!-- AbiWord is a free, Open Source word processor. -->

<!-- You may obtain more information about AbiWord

at www.abisource.com -->

<!-- ================================================== -->

<chapter>

<title></title>

<section role="unnumbered">

<title></title>

<para>You can of course buy and install a fully-fledged

commercial XML editor with XSLT support, and run this

application within it. However, this is beyond the

reach of many users, so to do this unaided you just

need to install three pieces of software: <ulink

url="http://java.com/download/"><emphasis>Java</emphasis></ulink>,

<ulink

url="http://saxon.sourceforge.net"><emphasis>Saxon</emphasis></ulink>,

and the <ulink

url="http://www.docbook.org/xml/4.2/index.html">DocBook

4.2 DTD</ulink> (URIs are correct at the time of writing).

None of these has a visual interface: they are run from

the command-line in the same way as is possible with

L<superscript>A</superscript>T<subscript>E</subscript>X.</para>

</section>

</chapter>

</book>The XSLT language lets us create

templates for each type of element in an XML document. In our example, there are only

three which need handling, as we did not create chapter or

section titles (DocBook requires them to be present, but

they don’t have to be used).

para, for the paragraph[s];

ulink, for the URIs;

emphasis, for the italicisation.

I’m going to cheat over the superscripting and

subscripting of the letters in the LATEX logo, and use my

editor to replace the whole thing with the

\LaTeX command. In the other three cases,

we already know how LATEX deals with these, so we can

write the templates accordingly.

Writing XSLT is not hard, but

requires a little learning. The output method here is

text, which is LATEX’s file format

(XSLT can also output

HTML and other flavours of

XML).

<xsl:stylesheet xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform"

version="2.0">

<xsl:output method="text"/>

<xsl:template match="/">

<xsl:text>\documentclass{article}\usepackage{url}</xsl:text>

<xsl:apply-templates/>

</xsl:template>

<xsl:template match="book">

<xsl:text>\begin{document}</xsl:text>

<xsl:apply-templates/>

<xsl:text>\end{document}</xsl:text>

</xsl:template>

<xsl:template match="para">

<xsl:apply-templates/>

<xsl:text>

</xsl:text>

</xsl:template>

<xsl:template match="ulink">

<xsl:apply-templates/>

<xsl:text>\footnote{\url{</xsl:text>

<xsl:value-of select="@url"/>

<xsl:text>}}</xsl:text>

</xsl:template>

<xsl:template match="emphasis">

<xsl:text>\emph{</xsl:text>

<xsl:apply-templates/>

<xsl:text>}</xsl:text>

</xsl:template>

</xsl:stylesheet>The first template matches /, which is

the document root (before the book

start-tag). At this stage we output the text which will

start the LATEX document,

\documentclass{article} and

\usepackage{url}.

The apply-templates instructions tells

the processor to carry on processing, looking for more

matches. XML comments get ignored,

and any elements which don’t match a template simply

have their contents passed through until the next match

occurs, or until plain text is encountered (and

output).

The book template outputs the

\begin{document} command, invokes

apply-templates to make it carry on

processing the contents of the book element,

and then at the end, outputs the

\end{document} command.

The para template just outputs its

content, but follows it with a linebreak, using the

hexadecimal character code x0A.

The ulink template outputs its content

but follows it with a footnote using the

\url command to output the value of

the url attribute.

The emphasis template surrounds its

content with \emph{ and

}.

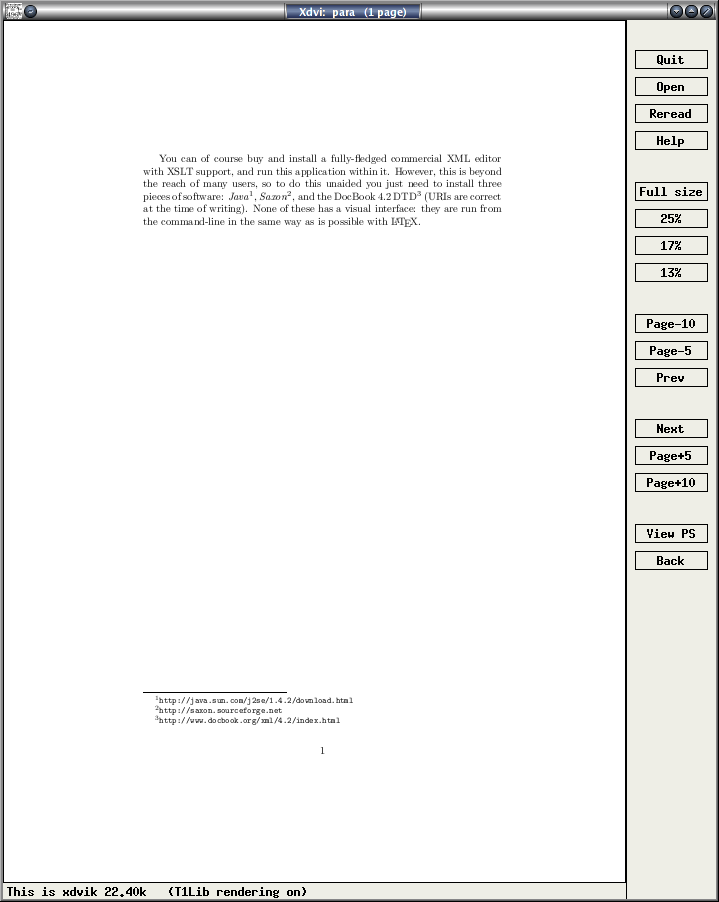

If you run this through

Saxon, which is an

XSLT processor, you can output a LATEX

file which you can typeset (see Figure 8.4 below).

$ java -jar saxon-he-10.3.jar -o para.ltx para.dbk para.xsl

$ xelatex para.ltx

This is XeTeX, Version 3.14159265-2.6-0.999991 (TeX Live

2019/Debian) (preloaded format=xelatex) \write18 enabled.

entering extended mode

LaTeX2e <2020-02-02> patch level 2

L3 programming layer <2020-02-14>

(./para.tex

(/usr/share/texlive/texmf-dist/tex/latex/base/article.cls

Document Class: article 2019/12/20 v1.4l

Standard LaTeX document class

(/usr/share/texlive/texmf-dist/tex/latex/base/size11.clo))

(/home/peter/texmf/tex/latex/geometry/geometry.sty

(/usr/share/texlive/texmf-dist/tex/latex/graphics/keyval.sty)

(/usr/share/texlive/texmf-dist/tex/generic/iftex/ifpdf.sty

(/usr/share/texlive/texmf-dist/tex/generic/iftex/iftex.sty))

(/usr/share/texlive/texmf-dist/tex/generic/iftex/ifvtex.sty)

(/usr/share/texlive/texmf-dist/tex/generic/iftex/ifxetex.sty)

(/home/peter/texmf/tex/latex/geometry/geometry.cfg))

(/usr/share/texlive/texmf-dist/tex/latex/base/textcomp.sty)

(/usr/share/texlive/texmf-dist/tex/latex/l3backend/l3backend-xdvipdfmx.def)

(./para.aux)

(/usr/share/texlive/texmf-dist/tex/latex/base/ts1cmr.fd)

*geometry* driver: auto-detecting

*geometry* detected driver: xetex

[1] (./para.aux) )

Output written on para.pdf (1 page).

Transcript written on para.log.

$

Figure 8.4: The typeset paragraph and its generated source

code

\documentclass{article}\usepackage{url}\begin{document}

You can of course buy and install a fully-fledged commercial XML

editor with XSLT support, and run this application within it. However,

this is beyond the reach of many users, so to do this unaided you just

need to install three pieces of software:

\emph{Java}\footnote{\url{http://java.sun.com/j2se/1.4.2/download.html}},

\emph{Saxon}\footnote{\url{http://saxon.sourceforge.net}}, and the

DocBook 4.2

DTD\footnote{\url{http://www.docbook.org/xml/4.2/index.html}} (links

are correct at the time of writing). None of these has a graphical

interface: they are run from the command-line in the same way as is

possible with \LaTeX.

\end{document}

This is a relatively trivial example, but it serves to

show that it’s not hard to output LATEX from

XML — this document is produced in

exactly this way.