LATEX’s internal measurement system is extremely

accurate. The underlying TEX engine conducts all its

business in units smaller than the wavelength of visible

light, so if you ask for 15mm space, that’s what you’ll

get — within the limitations of your screen or printer, of

course. While modern high-resolution displays use pixels

smaller than you can easily see, many older screens cannot

show dimensions of less than 1⁄96″ without resorting to magnification or

scaling; and on printers, even at 600dpi, fine oblique lines

or curves can still sometimes be seen to stagger the

dots.

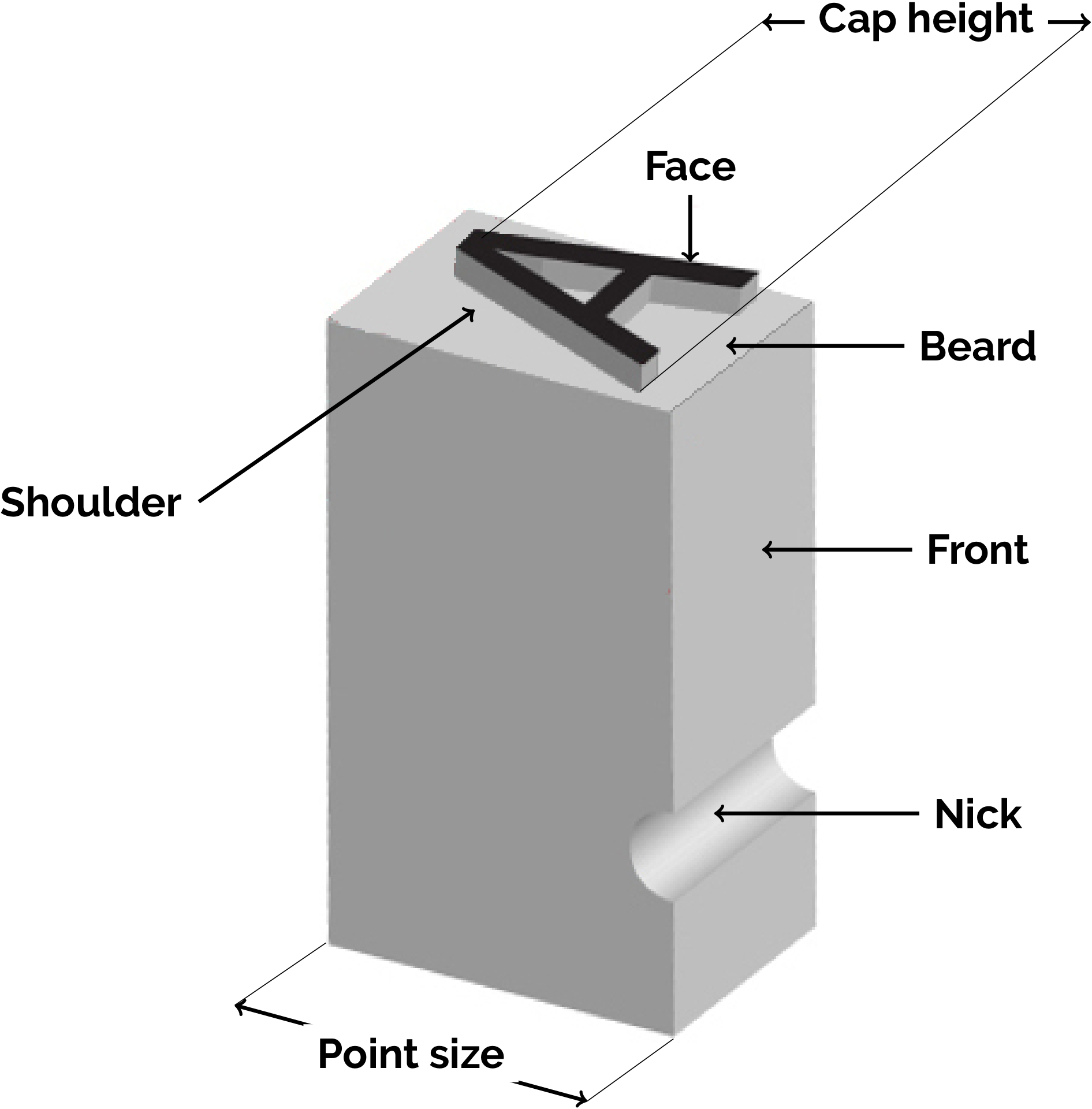

Figure 1.3: Some parts of a piece of metal type

At the same time, many dimensions in LATEX’s

preprogrammed formatting are specially set up to be flexible:

so much space, plus or minus certain limits to allow the

system to make its own adjustments to accommodate variations

like overlong lines, unevenly-sized images, displayed

equations, and non-uniform spacing around headings. This is

very different from the ‘grid’ system

used in many other typesetting and DTP

systems.

TEX uses a very sophisticated justification algorithm to

achieve a smooth, even texture to normal paragraph text by

justifying a whole paragraph at a time, quite unlike the

line-by-line approach used in most wordprocessors and

DTP systems.

Occasionally, however, you will need to hand-correct an

unusual word-break or line-break, and there are facilities for

doing this on individual occasions as well as automating it

for use throughout a document.

1.10.1 Specifying size units

Most people in the printing and publishing industry in

English-speaking cultures habitually use the traditional

printers’ points,

picas and ems

as well as cm and mm when dealing with clients. Many older

English-language speakers (and most North Americans) still

use inches. In continental European and related cultures,

Didot points and Ciceros (Didot picas) are also used

professionally, but cm and mm are standard everywhere else:

inches are largely obsolete and only used now when

communicating with North American cultures.

Table 1.4: Units in LATEX

| Unit | Size |

| Printers’ fixed measures |

| pt | Anglo-American standard points (72.27 to the

inch) |

| pc | Pica ems (12pt) |

| bp | Adobe’s ‘big’ points

(exactly 72 to the inch) |

| sp | TEX’s internal

‘scaled’ points (65,536 to

the pt) |

| dd | Didot (European standard) points (67.54 to the

inch) |

| cc | Ciceros (European pica ems), 12dd) |

| Printers’ relative measures |

| em | Ems of the current point size (historically the

width of a letter ‘M’ but see

Figure 1.4 below) |

| ex | x-height of the current font (height of a

letter ‘x’) |

| Other measures |

| cm | centimeters (2.54 to the inch) |

| mm | millimeters (25.4 to the inch) |

| in | inches (obsolete except in UK and parts of

North America) |

You can specify lengths in LATEX in any of these

units, plus some others (see Table 1.4 above).

The em can cause beginners some puzzlement because it’s

a relative measurement based on the

‘point size’ of the type, so 1em in

12pt type is half the size of 1em in 24pt type. The point

size of type itself is also historically misleading: it

refers to the depth of the metal body on which foundry type

was cast in the days of metal typesetting. It does

not refer to the visible height of the

letters themselves when printed (see Figure 1.3 above). So the letter-size of 10pt type in one

typeface can be radically different from 10pt type in

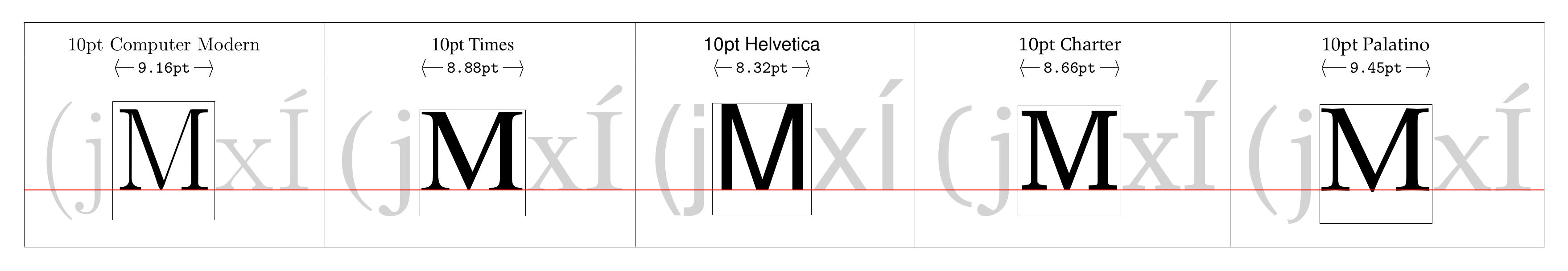

another (look at Figure 1.4 below, where the widths

are given for 10pt type).

An em is the height of the type-body in a specific size,

so 1em of 10pt type is 10pt and 1em of 18pt type is 18pt. A

1em space is called a ‘quad’, so a

24pt quad is 24pt×24pt. LATEX has a command

\quad for leaving exactly that much

horizontal space. A special name is given to the 12pt em

because it is so common: a ‘pica’ em

(from the old name for 12pt type). A pica has become a fixed

measure in its own right of exactly 12pt, and LATEX has a

dimension ‘pc’ for this, so 15pc is 15×12pt

long.

To highlight the differences between typefaces at the

same size, Figure 1.4 below shows five capital Ms in

different faces, surrounded by a box exactly 1em of those

sizes wide, and showing the actual width of each M when set

in 10pt type. Because of the different ways in which

typefaces are designed, none of them is exactly 10pt

wide.

Figure 1.4: An M of type of different faces boxed at 1em

The red line is the common baseline. Surrounding

letters in grey are for illustration of the actual

extent of the height and depth of one em of the current

type size.

If you are working with other DTP

users, watch out for those who think that Adobe points (bp)

are the only ones. The difference between an Adobe big-point

and the standard point is only .27pt per inch, but in 10″ of

text (a full page of A4) that’s 2.7pt, which is nearly 1mm,

enough to be clearly visible if you’re trying to align one

sample with another.

1.10.2 Hyphenation

LATEX hyphenates automatically according to the

language you use (see § 1.10.6 below). To specify

different breakpoints for an individual word, you can insert

soft-hyphens (discretionary hyphens), done with the

\- command (backslash-hyphen) wherever you

need them, for example:

When in Mexico, we visited Popo\-ca\-tépetl by

helicopter.

If the words needs to be hyphenated, the best-fit of the

points will be used, and the rest ignored.

To specify hyphenation points for

all occurrences of a word in the

document, use the \hyphenation command in

your Preamble (see the sidebar ‘The Preamble’ above) with one or

more words as patterns in its argument, separated by spaces;

in this case using the normal hyphen to indicate permitted

break-points. This will even let you break

‘helico-

pter’ correctly.

\hyphenation{helico-pter Popo-ca-tépetl vol-ca-no}If you have frequent hyphenation problems with long,

unusual, or technical words, ask an expert about changing

the value of \spaceskip,

which controls the flexibility of the space between words.

This is not something you would normally want to do without

advice, as it can change the appearance of your document

quite significantly.

If you are using a lot of unbreakable text (see the next

section and also § 4.7.1 below) it may also

cause justification problems: you can turn justification off

with \raggedright.

1.10.3 Breakable and unbreakable text

Unbreakable text is the opposite of discretionary

hyphenation. To force LATEX to treat a word as

unbreakable, use the \mbox command:

\mbox{pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis}This may have undesirable results, however, if you

subsequently change margins or the size of the text:

pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis,

although if you’re reading this in a browser, you probably

won’t see the effect properly: look at the PDF.

Another option, for reoccurring words, is to use the

\hyphenation command as shown in § 1.10.2 above, but give the word[s] with no hyphens at all,

which stops them having any break-points.

To tie two words together with an unbreakable

space (hard space), use a tilde

(~) instead of the space (see the

list in § 1.7 above). This will

print as a normal space but LATEX will never break the

line at that point.

A normal space between words is always a candidate for a

place to break the text into lines, and the word-spacing

gets evened-out between all the remaining words in the

paragraph (not just the line)...with one exception: a

full point (period) after a lowercase letter is treated in

LATEX as the end of a sentence, and it automatically gets

a little more space before the next word. You do not (indeed

SHOULD NOT) type any extra

space yourself between sentences.

However, after abbreviations in mid-sentence like

‘Prof.’, it’s

not the end of a sentence, so we need a

way to tell LATEX that this should be a normal space. The

command for doing this is the

\␣ (backslash-space — I have made the

space visible here so you can see it, but it’s just a normal

space). This prevents LATEX from adding the extra

sentence-space and it also means it becomes a normal

breakpoint (otherwise you would use the tilde as described

above).

For example, it would look odd to split the author’s

name

Prof. D.E.

Knuth

over a line-end. It’s a good idea to make adding

the non-sentence space standard typing practice for things

like people’s initials followed by their surname, as

Prof.\␣D.E.~Knuth (I've used a visible space character here for emphasis but you just type a normal space).

1.10.4 Dashes

The hyphen (-) is only used for hyphenated compound

words like editor-in-chief. LATEX inserts its own hyphens

when it needs to break a word at right right-hand

margin.

Dashes are different: they’re longer and they are used

in different places. Check the sidebar ‘If you don’t have accented letters on your

keyboard’ above for

how to find these characters in your computer’s

character-map.

- Long dash

The long dash — what printers call an

‘em rule’ like this — is used to separate a short

phrase from the surrounding text in a similar way to

parentheses. If you’re using LuaLATEX, you can just

type the long dash on your keyboard.

If you can’t find the character, type three

hyphens typed together, like---this:

LATEX will recognise this combination and

replace it with a real em rule.

If you want space either side, bind the first

hyphen to the preceding word with a tilde

like~---␣this and use a normal space

after the third hyphen (shown as a visible space

here, but it’s just a normal space). This avoids

the line being broken before the dash.

The difference between spaced and unspaced rules

is purely æsthetic, but different cultures have

different conventions (see the tip ‘Em rules vs En

rules’ below).

NEVER use a single

hyphen for this purpose.

Em rules vs En

rules

In a discussion on the TYPO-L mailing list,

Yateendra Joshi observed:

[…] unspaced em dashes are standard in US

publishing, whether the dashes occur in pairs enclosing

parenthetical matter or come singly before the last part

of a sentence. In the UK and Europe, I often see spaced

en dashes when they occur in pairs but an unspaced em

dash when it occurs singly.

Leila Singleton wrote:

[…] unspaced dashes are the standard for the US

publishing industry, as it typically references the MLA

Handbook (used by books + journals) to establish

stylistic conventions. It's worth mentioning that the

Associated Press Stylebook (used for newspapers and

sometime magazines) instead calls for spaces. It's my

understanding that an en dash in British usage is

equivalent to an em dash in American usage, and that

it's spaced whether it appears as a single or a

pair …

Christopher R Maden wrote:

[I learned] that

Jan Tschichold’s

influential design for Penguin Books included spaced

en-dashes instead of em-dashes, and that directive (and

a few others) saw wide uptake throughout British

typography.

- Short dash

The short dash is used between digits like page ranges

(35–47). Printers call this an

‘en rule’ and if you’re not using LuaLATEX you can get

it by typing two hyphens together, as in

35--47.

NEVER use a single

hyphen for this purpose either.

- Minus sign

If you want a minus sign, use math mode (see § 1.11 below) where you type a normal hyphen as

part of a mathematical expression, so it occurs between

math delimiters like \(x=y-z\) for

x=y-z. DO

NOT use the hyphen for a minus sign

outside math mode.

There are other dashes for special purposes in the

Unicode repertoire, but they are out of scope for this

document.

1.10.5 Justification

The default mode for typesetting in LATEX is justified

(two parallel margins, with word-spacing adjusted

automatically for the best optical fit). In justifying,

LATEX will never add space between letters, only between

words. The soul package can be used if

you need letter-spacing (‘tracking’),

but this is best left to the expert.

There are two commands

\raggedright and

\raggedleft which typeset with only one

margin aligned. Ragged-right has the text ranged (aligned)

on the left, and ragged-left has it aligned on the right.

They MUST be used inside a

group (curly-braces, for example: see

the sidebar ‘Grouping’ below) to confine their action to a

part of your text, otherwise all the rest of the document

will be done that way. Put the command in your Preamble if

you want the whole document like that. This paragraph is set

ragged-right.

These modes also exist as environments called

raggedright and raggedleft

which are more convenient when applying this formatting to a

whole paragraph or more, like this one, set

ragged-left.

\begin{raggedleft}

These modes also exist as environments

called raggedright and raggedleft which is more

convenient when applying this formatting to a

whole paragraph or more, like this one.

\end{raggedleft}Ragged setting turns off hyphenation and indentation.

There is a package ragged2e providing the

command \RaggedRight (note the

capitalisation) which retains hyphenation in ragged setting,

useful when you have a lot of long words. There’s a

\RaggedLeft and a

\RaggedCenter, too.

To centre text, which is in effect both ragged-right and

ragged-left at the same time, use the

\centering command inside a

group, or use the

center environment.

Be careful when centering headings or

other display-size

material: it’s one of the rare occasions when you may need

to add a premature linebreak or forced newline

(the double-backslash \\) to make the lines

break at sensible pauses in

the meaning

(Flynn, 2012). Never

rely on the automated

line-breaking of editors in these cases.

White-space and the double backslash

The \\ command is

not the same as a paragraph

break: it’s just a premature linebreak

within the current paragraph. The

double backslash command can have an optional argument (in

square brackets) giving an amount of extra white-space to

leave, if you need to, eg

not the same as a paragraph break\\[3mm]

it's just a premature linebreak

(If you need to start the new line with a square

bracket for some reason, you will need to

prefix it with an empty group ({}) to prevent

it being interpreted as the optional argument to

\\.)

1.10.6 Languages

LATEX can typeset in the native manner for several

dozen languages. This affects hyphenation, word-spacing,

indentation, and the automatic labelling of the parts of

documents displayed in headings such as Chapter, Appendix,

References, etc (but not the commands used to produce

them).

Most distributions of LATEX come with

US English and one or more other

languages installed by default, but it is easy to use the

babel or polyglossia

package and specify any of the supported languages or

variants, for example with babel:

\usepackage[german,frenchb,english]{babel}

...

As one writer has noted, \selectlanguage{german}``Das

berühmte Voltaire-Zitat, \emph{\foreignlanguage{frenchb}

{il est bon de tuer de temps en temps un amiral pour

encourager les autres}}, ist ein Beispiel sarkastischer

Ironie.''\selectlanguage{english}yMake sure that the base language of the document comes

last in the list. The list of supported

languages is in the package documentation. The syntax is

similar for polyglossia but a little more

explicit:

\usepackage{polyglossia}

\setmainlanguage{english}

\setotherlanguage{german}

\setotherlanguage{french}

\begin{document}

As one writer has noted, \textlang{german}{``Das

berühmte Voltaire-Zitat, \emph{\textfrench{il est

bon de tuer de temps en temps un amiral pour

encourager les autres}}, ist ein Beispiel sarkastischer

Ironie.''}Changing the language with babel or

polyglossia is a cultural shift: it

changes the hyphenation patterns, the word-spacing, the way

in which indentation is used, and the names of the

structural units and identifiers like

‘Abstract’,

‘Chapter’, and

‘Index’, etc. For example, using

French as the default, chapters will start with

‘Chapitre’.

Both packages provide scoped and unscoped commands as

shown in the examples to let you tell LATEX when to switch

to the language specified in the argument. If you have only

a small fragment in another language (a word or two, maybe a

sentence, but less than a paragraph), use the scoped command

with the first argument giving the language and the second

with the word or phrase. For longer passages (more than a

paragraph), use the unscoped command, with just the

language, and then another unscoped command to switch back

to the main language afterwards.

These packages use the hyphenation patterns provided

with your version of LATEX (see the start of your document

log files for a list). For other languages you need to set

the hyphenation separately (outside the scope of this

book).