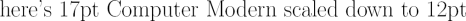

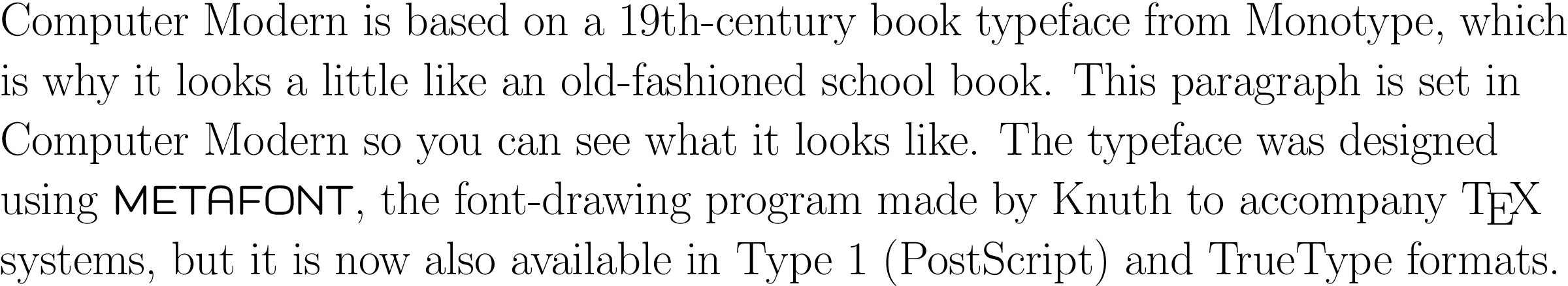

The default typeface in LATEX is Computer Modern (CM). This typeface was

created by Knuth for use with TEX. It is based on a

Victorian book typeface, Monotype Series 8, because he

designed TEX originally for typesetting books. Because it is

one of the very few book typefaces with a comprehensive set of

mathematical fonts, it has remained the default, rather than

the variations on Times that you find in wordprocessors and

other DTP systems — until recently the full

set of mathematical symbols for Times was an expensive

commercial add-on.

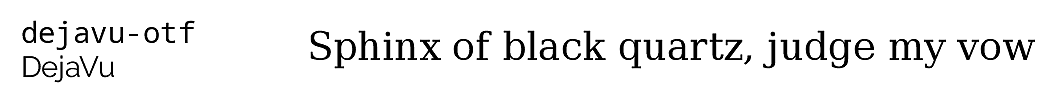

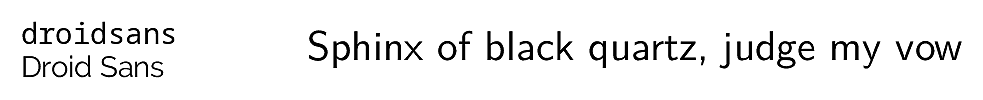

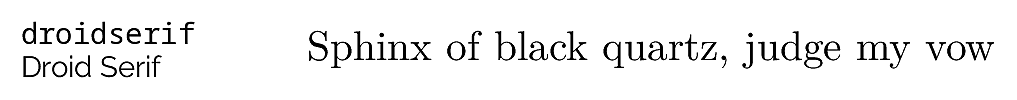

The standard distribution of TEX Live comes with about

130 OTF and 75 TTF

typefaces (see § 6.2.2.1 below). There are

also some 300 obsolescent Postscript (PS)

Type 1 typefaces (many of these are the PS

versions of the OTF and

TTF faces), plus about 165 legacy

METAFONT (PS Type 3) fonts, to preserve

compatibility with older documents which still need to use

them.

LATEX can use more different types of font than any

other system

The original LATEX used METAFONT fonts (before

PS, TTF, or

OTF formats were invented)

pdfLATEX could use any METAFONT or

PS Type 1 font;

XƎLATEX and LuaLATEX can use any METAFONT or

PS Type 1 or TTF

or OTF font.

6.2.1 First time only: setting up fonts

for Lua

LATEXLuaLATEX lets you use all your system fonts — those

that came preinstalled with your computer and your other

(non-TEX) software — as well as the ones that came with

your TEX distribution.

The very first time you run LuaLATEX there will

be a pause while it indexes all your fonts. It

will then continue to process your document.

After the first time, if you install a new font, and

then use it in a LATEX document, LuaLATEX will re-index

your fonts so that the new one is included, and then

continue normally.

6.2.2 Set the default font family for a document

As explained in § 6.2 (this section), Computer

Modern is the built-in default typeface, so that’s what you

get if you don’t specify anything else. There are three ways

to specify other typefaces and individual fonts:

a ) by using a package; b ) by font name; or c ) by filename.

Using a package is the most convenient, especially for

whole typefaces, because the configuration of all the

component fonts (eg roman, italic, bold, bold-italic, math,

etc) has already been done by the package author. In cases

where a package does not exist for a typeface or font, you

need to know the font name: use your system’s font display

utility to find it. In more complex cases you can use the

font filename[s] but you may need to know what directory

they are installed in.

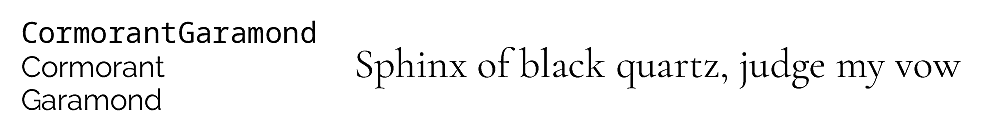

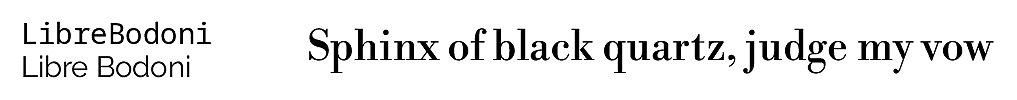

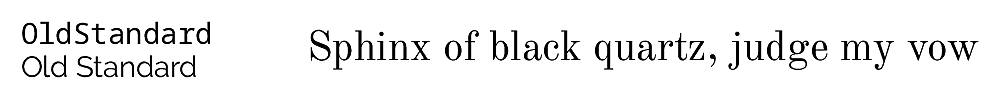

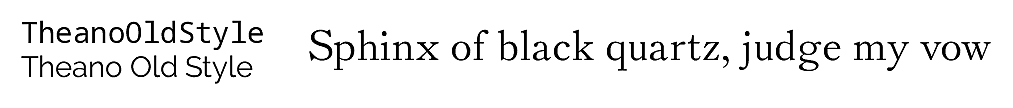

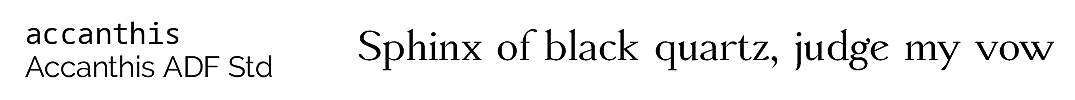

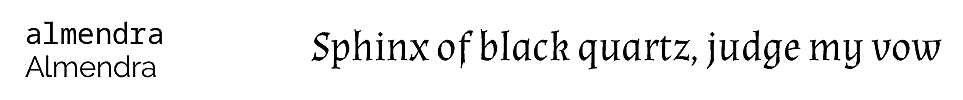

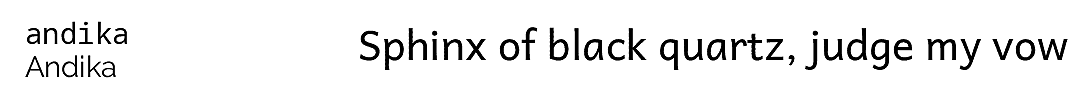

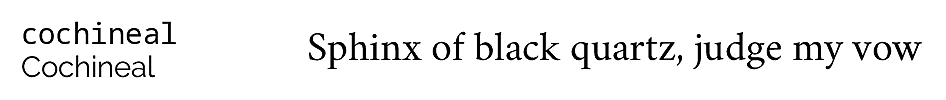

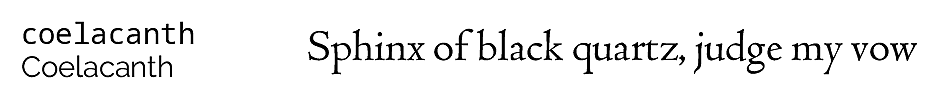

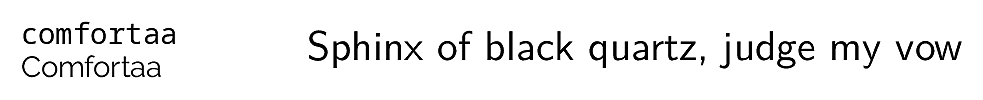

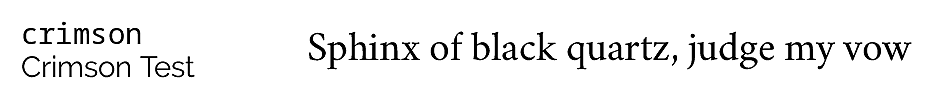

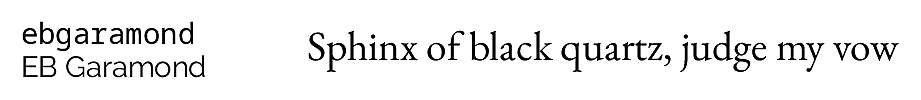

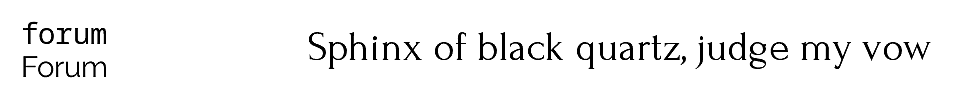

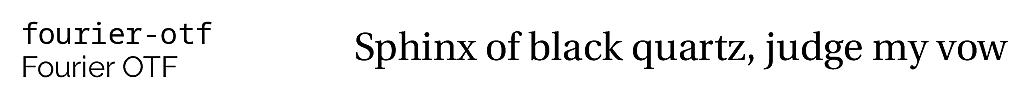

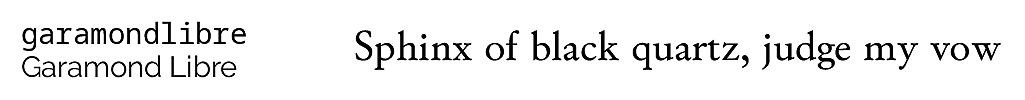

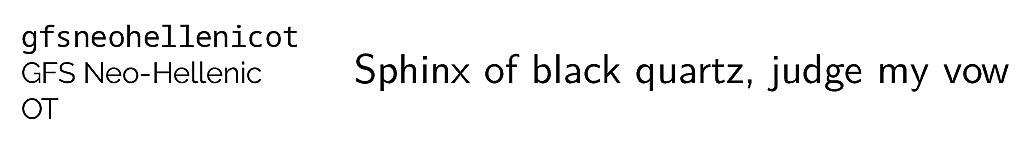

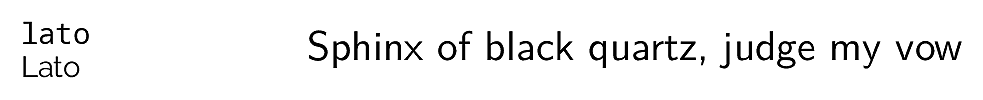

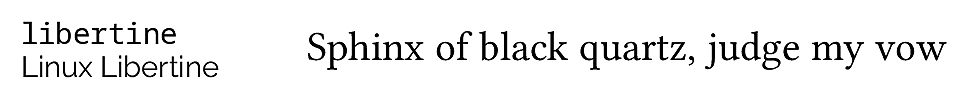

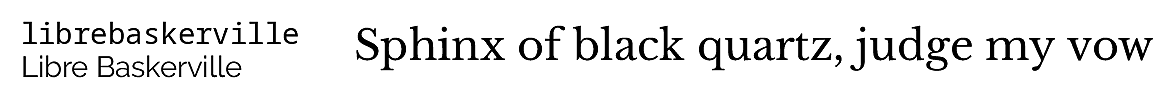

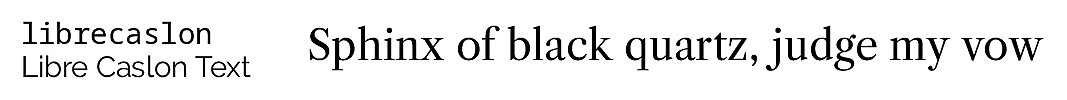

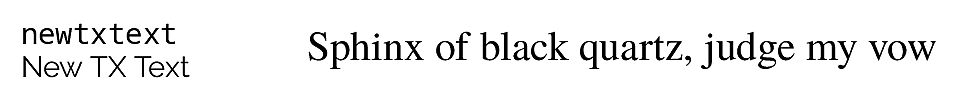

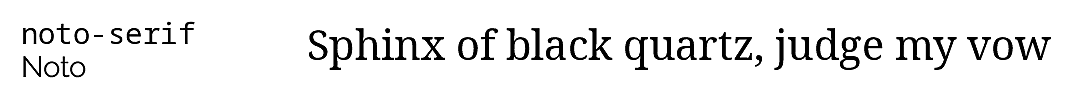

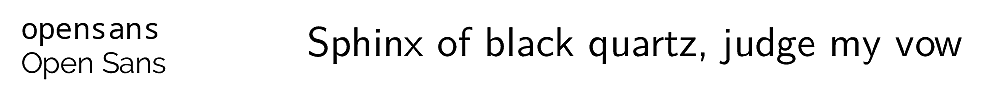

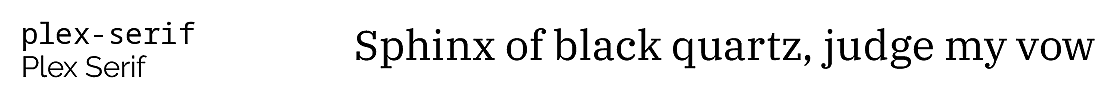

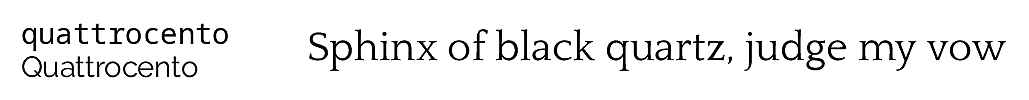

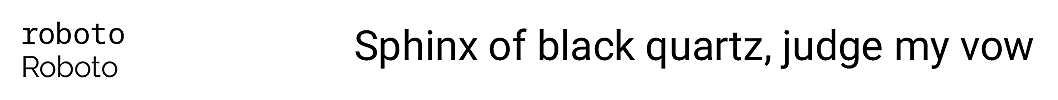

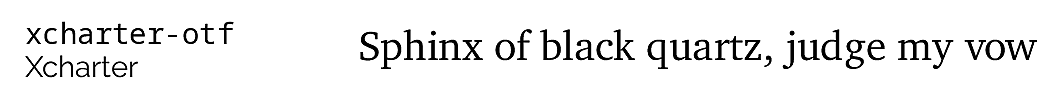

6.2.2.1 OpenType and TrueType typeface packages for LATEX

The list below shows the 60

or so packages for OTF and

TTF typefaces which are

installed with a full distribution of TEX. Because these

are packages, using one makes the

typeface immediately available, eg

\usepackage{ebgaramond}will set the EB Garamond typeface as the default for

the document. For packages setting a sans-serif typeface

(not normally used as a default), there is usually a

default option which does it, eg

\usepackage{roboto}Many of these packages include many variants of te

typeface beyond the conventional roman, italic, bold, and

bold-italic: it’s important to read the package

documentation to find out what is available.

(Some specialist font packages are not included here

because they are not actually fonts in themselves, but

‘enabling’ packages which make

specific combinations available for special purposes, such

as the hep-font package for math

combinations for the High Energy Physics

community.)

Adobe

‘35’ font equivalents

LATEX also includes versions of the popular (some

would say overused) Adobe ‘35’

fonts which have been built into laser printers,

wordprocessors, PDF readers, printer

drivers, and most DTP systems since the

dawn of desktop publishing shortly after TEX was

written. I am listing them separately because they are

still much asked-after, although their popularity has

waned as wordprocessors now provide other typefaces.

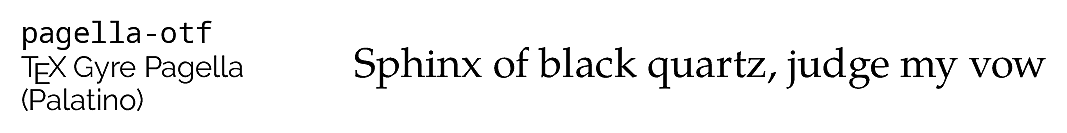

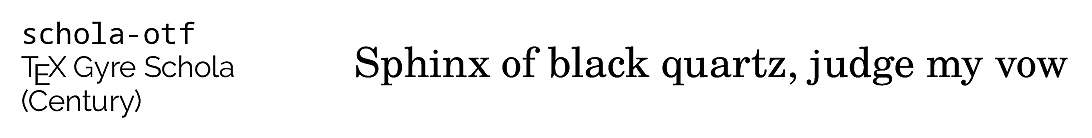

Four of the most often-requested are available as

packages in the list above: Century Schoolbook

(schola-otf), Helvetica

(heros-otf), Palatino

(pagella-otf), and Times New Roman

(termes-otf). The rest can be used

with the commands listed in Table 6.2 below.

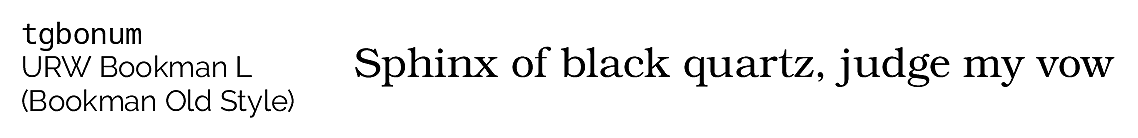

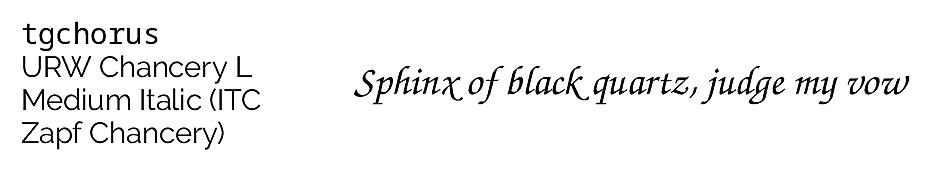

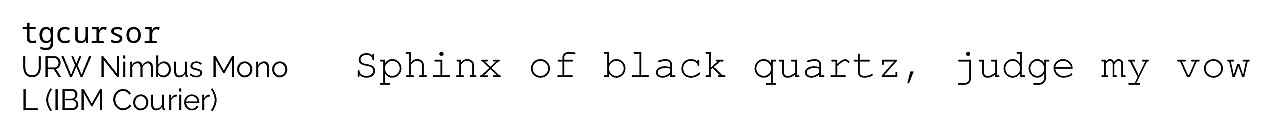

The collection comprises six text typefaces (four

serif and two sans-serif, each in roman, italic, bold, and

bold-italic, making 32 fonts) plus one monospace, one

script, and one dingbats (35 fonts in total). For

copyright reasons they are now provided by

carefully-matched non-Adobe versions known as the

‘TEX Gyre’ collection, derived

from the equivalents generously donated by URW (Unternehmensberatung Rubow

Weber).

Table 6.2: The Adobe ‘35’ fonts

| TEX Gyre name | Font name | Adobe name | Package | Command |

| Adventor | URW Gothic L | Avant Garde | | \setsansfont{TeX Gyre Adventor} |

| Bonum | URW Bookman L | Bookman Old Style | | \setmainfont{TeX Gyre Bonum} |

| Chorus | URW Chancery L | Zapf Chancery | | \newfontface{\chancery}{TeX Gyre Chorus} |

| Cursor | URW Nimbus Mono | IBM Courier | | \setmonofont{TeX Gyre Cursor} |

| Heros | URW Nimbus Sans L | Helvetica | heros-otf | |

| Pagella | URW Palladio L | Palatino | pagella-otf | |

| Schola | URW Century Schoolbook L | Century Schoolbook | schola-otf | |

| Termes | URW Nimbus Roman No9 L | Times New Roman | termes-otf | |

| — | Pi Font | Zapf Dingbats | | See below |

The 35th font, Zapf Dingbats, is not included in the

TEX Gyre Collection, as it is now largely superseded by

LATEX’s own collection of symbols (see

(Pakin, 2009)) but the

bbding and marvosym

packages provide many replacements and

alternatives.

If you need the old Microsoft Symbol font, it can be

downloaded,

but Scott Pakin’s Comprehensive

LATEX Symbol List is probably a better place to

find symbols.

Exercise 6.1 — Try some font packages

Experiment with changing your typeface.

Put a \usepackage command in your

document’s Preamble, and retypeset it, for example:

\usepackage{Caladea}Notice how the typefaces are all different widths,

so the spacing and line-ends may change.

You can only use one of these packages at a time for

a class of font (seif, sans-serif, or monospace). Using

another of the same class just overrides the previous

one.

6.2.2.2 OpenType and TrueType fonts and faces by fontname

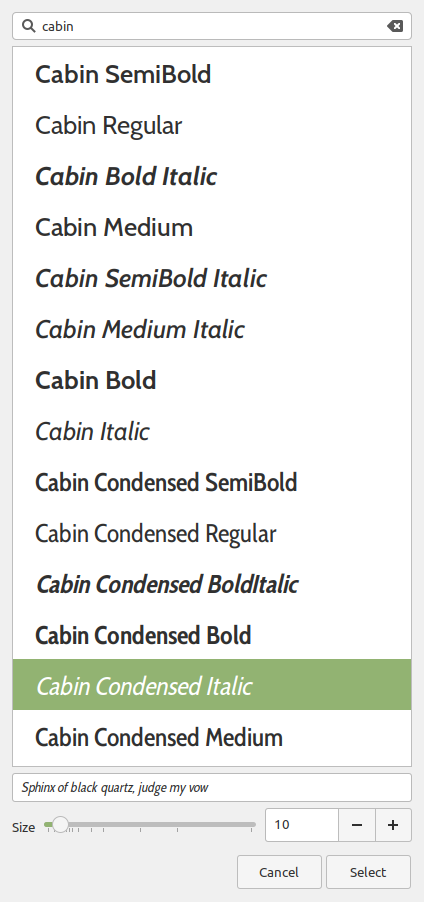

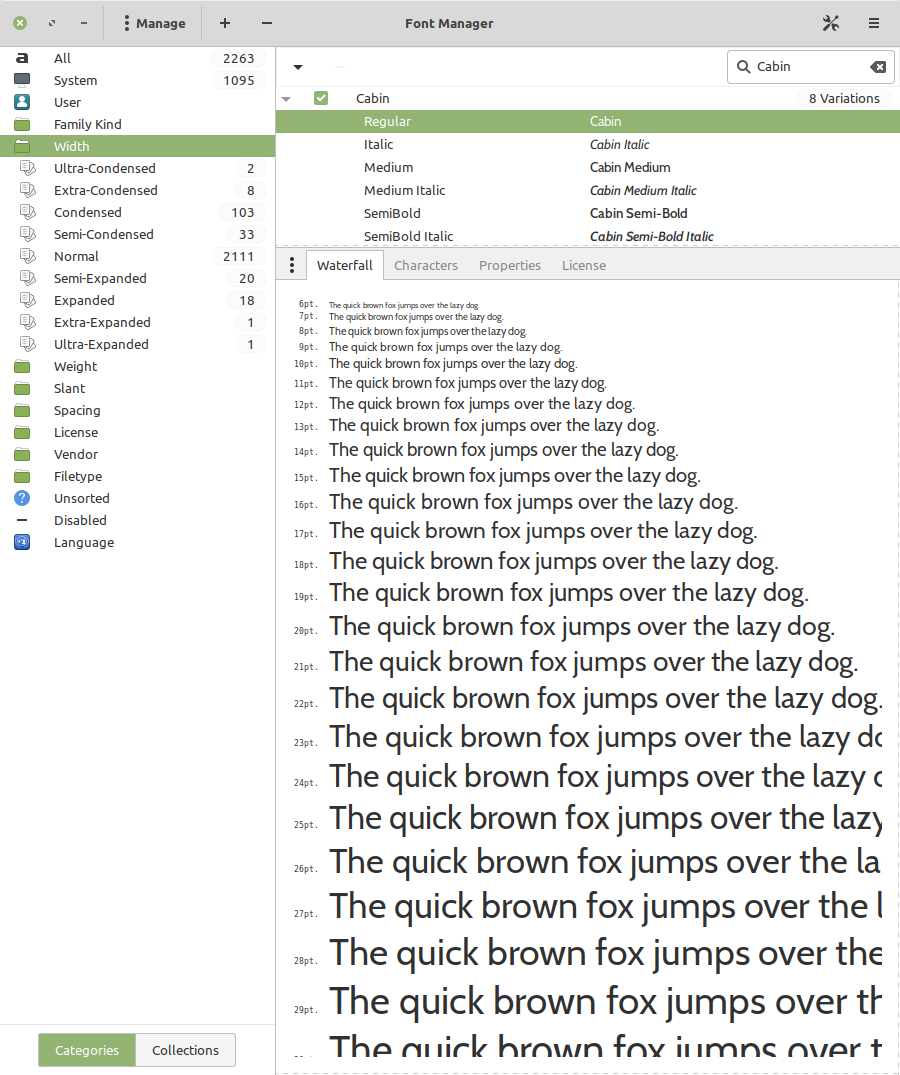

The fontname of a font is the

name that the designer declares is the name of the font

family (like Cabin), or sometimes the name of the

individual font (like Almendra-Bold). It is

not the filename, although sometimes

they happen to be the same. The fontname is the name you

see in lists of fonts like the font dialog drop-down

menu in editors.

You need the fontspec package to

use OT and TT faces

and fonts by fontname. This package provides three

commands to select font families:

\setmainfont (for the roman or main

face); \setsansfont (for the sans-serif

face); and \setmonofont (for the

typewriter or monospace face). These all take one

compulsory argument: the fontname of the font family or

typeface (we will see in § 6.2.2.3 below

how to do this with filenames).

You can find the fontnames of any of your installed

fonts by using your font browser or indexing command

provided by your operating system.

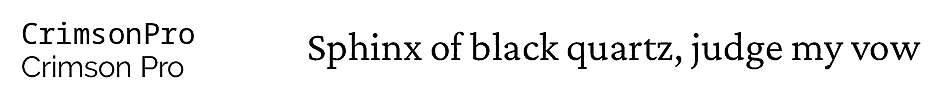

Exercise 6.2 — Try setting up fonts by fontname

Open a new LATEX file in your editor (pick a

blank or epty one if your editor offers

templates)

Copy and paste this text into the file:

\documentclass[12pt]{article}

\usepackage{fontspec}

\setmainfont{Crimson Pro}

\setsansfont{Cabin Regular}

\setmonofont{TeX Gyre Cursor}

\AtBeginDocument{\LARGE}

\begin{document}

This is the main (default) font

\sffamily This is the sans-serif font

\ttfamily This is the monospace font

\end{document}Process the document and examine the

PDF. You may notice that the

sans-serif font (Cabin) and the monospace font

(Cursor)looks larger than the main font (Crimson),

even though they are all set to the

\LARGE size (about 18pt, see

Table 6.5 below). This is because fonts are

designed with different heights to the lowercase and

uppercase characters.

Compensate for this by adding the option

Scale=MatchLowercase to the sans

and mono commands:

\setsansfont{Cabin Regular}[Scale=MatchLowercase]

\setmonofont{TeX Gyre Cursor}[Scale=MatchLowercase]Reprocess and see that the sans and mono fonts

have now been loaded at a size which matches the

main font

There are packages for four of the TEX Gyre

fonts, as noted in Table 6.2 above.

6.2.2.3 OpenType and TrueType fonts and faces by

filename

This section is temporarily withdrawn

6.2.3 Changing the font-family temporarily

To use a different font [family] for a specific purpose,

use the command \newfontfamily. This works

exactly the same as the commands above for setting the main,

sans, and mono font families but takes an extra parameter

first, to specify the command you want it known by, so it

does not replace the Roman, Sand, or

Monospace defaults but is available in

addition to them. To make the command

\tablesfont invoke Liberation Sans

Narrow, for example, you would use:

\newfontfamily{\tablesfont}{Liberation Sans Narrow}Then the new command (here,

\tablesfont) can be used to switch to that

typeface.

To load a solitary font (that is, not a whole family),

there is a command \newfontface, which also

works in the same way, by creating a new command to switch

to it.

These commands created by

\newfontfamily, like the ones in Table 6.3 below, are called

‘unscoped’ because they have global

effect from that point on. In order to restrict the effect

to a smaller scope (a few words, for example), you

MUST put the command

and the text inside a

group (enclosed in curly braces as in

the example, or within an environment), otherwise they will

apply to the end of the document. See the sidebar ‘Grouping’ below for more detail.

In a normal document, of course, arbitrary typeface

changes like this are rare: people don’t (or at least,

probably shouldn’t) randomly flip from one font to another.

You select your default typefaces once, using packages or

commands, at the start of the document, and stick with

them — bold and italics are handled by the document class or

stylesheet packages you use.

However, in advertising or magazines, a wide range of

typefaces changes is common, but they are usually part of

predefined styles for handling that type of formatting,

built into the document class, so it is rare to have to do

them manually.

Most cases where people want unusual typeface

changes involve things like special symbols or effects on a

repetitive basis, and LATEX provides much easier

(programmable) ways to make these changes into shorthand

commands (called macros: see Chapter 7 ‘Programmability’ below).

This is jumping ahead a bit, but you could, for example,

define a new macro called \product which

would let you typeset product names in a distinct typeface

(usually italics):

Andlinger, Inc., has replaced \product{Splosh} with

\product{SuperSplosh}.This is one of LATEX’s most powerful features.

It means that if you needed to change your

\product command at some later stage to

use a different font, you only have to change

the font-family name in the macro, and

you don’t need to edit your document text at all.

What’s more, a macro could do other things at the same time,

like add an entry to an index of products.

Vastly more common are changes to type

style, while staying within the same

font-family.

6.2.4 Changing type style

Within each typeface or font family there are usually

several different ‘looks’ to the type

design. LATEX distinguishes mainly between font shape and font series.

Italics is a shape (look carefully: the

actual shape of the letters changes, as well as their

slope); whereas bold is a series

(same shapes, same slope, just thicker strokes).

Beware of pushing your fonts beyond their limits unless you

have typographic skills. It is not normally meaningful to combine

one shape or series class with another of the same class,

such as trying to get slanted-italics. It’s also sometimes

impossible to combine one family with another (such as

seriffed sans-serif type!). Slanted plus italics, for

example, doesn’t make any sense, as italics are already

slanted; and while some typefaces may well possess

sans-serif italic

small caps, they are not in common use.

If you really feel you need such combinations, try the

fontaxes package, which splits the

‘shape’ axis into a primary axis

(upright, italic, slanted, upright italic, etc) and a

secondary axis (small caps on or off). It redefines the

\itshape and \scshape

commands to combine instead of override each other. The

fontspec package loads

fontaxes. So do many legacy font

packages. (Thanks to @Davislor on tex.stackexchange for this

information.)

Sans-serif and

monospace (typewriter) are not just different fonts, they

are often different typeface families entirely.

To avoid the problem of forgetting to put curly braces

around the commands and text you want

formatted, there is an alternative set of

scoped commands for the most common

type shape and series commands. These use curly braces in

the ‘argument’ manner, so their

effect applies only to the text in curly braces. These are

the normal commands for changing the style of a word or

phrase.

Table 6.4: Typeface styles, families, shapes, and series

(scoped)

| Type style | Command | Example (using Computer

Modern) |

| Italic | \textit{text} | puts text into

italics |

| Slanted | \textsl{text} | puts text into

slanted type* |

| Small Capitals | \textsc{text} | puts TEXT into

small caps |

| Bold | \textbf{text} | puts text into

bold type |

| Sans-serif | \textsf{text} | puts text

into sans-serif type |

| Monospace | \texttt{text} | puts text

into typewriter type |

These are commutative too, so you can nest them inside

one another:

...\textbf{bold \itshape{italic \textsf{sans-serif}}} type...What we know as

underlining isn’t a font: it was used

in the days of

typewriters where italics were not available, and

it is extremely rare in typography except for specialist

purposes. If you think you need it, use the

ulem package with the

normalem option, which provides a

\uline command.

6.2.5 Font sizes

LATEX has built into its defaults a set of predefined

font size steps corresponding more or less to the

traditional sizes available to metal typesetters. This is

deliberate, as these sizes have grown up over 500 years of

experience in printing as those which go best together for

book-work, which is where TEX originated.

Table 6.5: LATEX font step sizes

| Command | Example | Nominal point size | Exact point size |

| \tiny | The quick brown fox

jumps over the lazy dog | 5 | 5 |

| \scriptsize | The quick brown

fox jumps over the lazy dog | 7 | 7 |

| \footnotesize | The quick

brown fox jumps over the lazy dog | 8 | 8 |

| \small | The quick brown fox

jumps over the lazy dog | 9 | 9 |

| \normalsize | The quick

brown fox jumps over the lazy dog | 10 | 10 |

| \large | The quick brown fox

jumps over the lazy dog | 12 | 12 |

| \Large | The quick brown fox

jumps over the lazy dog | 14 | 14.40 |

| \LARGE | The quick brown

fox jumps over the lazy dog | 18 | 17.28 |

| \huge | The quick

brown fox jumps over the lazy dog | 20 | 20.74 |

|

\Huge | The quick

brown fox jumps over the lazy dog | 24 | 24.88 |

• Note that these are

unscoped commands (see the sidebar ‘Scope and style’ above), so they

should be used inside a group, either an environment

or a set of curly braces terminated with a

\par inside the closing brace. There

are no scoped equivalents of these commands.

• Mathematics users should not

confuse the text-mode \scriptsize

command here with mathematics-mode

\scriptstyle. [Thanks to

Doug McKenna and

David Carlisle on the TEXhax mailing

list.]

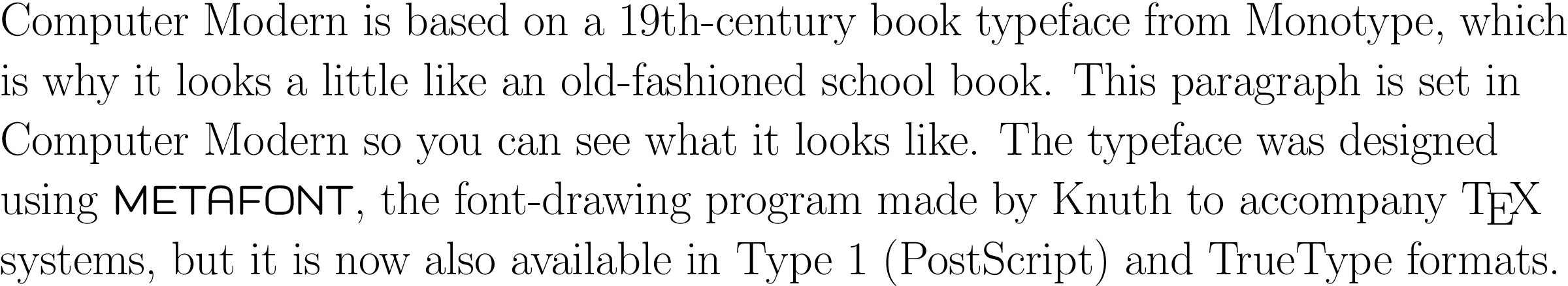

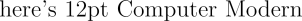

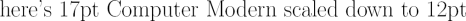

These sizes are also reflected in the size

steps at which Computer Modern was designed in

the METAFONT program. It often comes as a surprise to new

users that many typefaces are not designed as a single font

and just scaled up or down, but specially drawn at different

sizes to make them more legible.

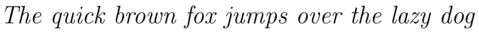

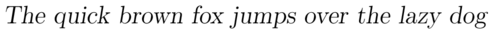

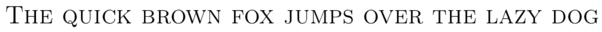

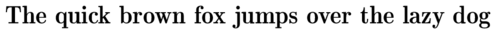

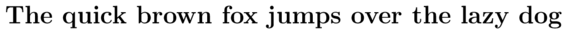

As an example,  , and

, and  ,

and

,

and  so you can see there really

is a significant difference.

so you can see there really

is a significant difference.

Modern type

formats have hinting parameters that

allow scaling to implement the effects of design-sizes,

but in general, you probably don’t want to go scaling

fonts too far beyond their design size because the spacing

will start to look very odd.

The default sizes (and the commands that operate

them) are based on the use of a 10pt font, which is the

default size for book work.

Using the larger document class options (11pt and

12pt) will use 11pt and 12pt designs (explicit or

hinted), with the other sizes (such as for headings)

rescaled to match.

The exact sizes used are listed in the macros in the

Class Option files size10.clo,

size11.clo and

size12.clo.

LATEX’s default fonts above 10pt are in fact

scaled by a factor of 1.2, as shown in the fourth column

of Table 6.5 above.

While these shorthand commands relieve the beginner of

having to worry about the appropriate point-size

for a given task, if you need very specific sizes you

can use the \fontsize command to specify

exact sizes. This takes two arguments: the point size and

the baseline distance. The example below gives you 22pt type

on a 28pt baseline (ie with 6pt extra space or

‘leading’ between the lines).

The term ‘leading’ comes from the old metal-type

practice of adding a strip of typemetal between the lines,

or casting the type on a deeper body, to increase the line

spacing, so it’s pronounced ‘ledding’ after the

metal.

If you are using

pdflatex or the original

latex processor, you will need to

use the fix-cm package to override the

step sizes. This needs special placement: it

MUST come at the start of the

document, even before the

\documentclass command, and

MUST be invoked with the

\RequirePackage command normally used only

by document class designers:

\RequirePackage{fix-cm}

\documentclass{article}

...6.2.6 Logical markup

All this playing around with fonts is very pretty but

you normally only do it for a reason, even if that reason is

just to be decorative. Italics, for example, are used for

many things:

| Cause | Effect |

| Foreign words | ex

officio |

| Scientific names | Ranunculus

ficaria |

| Emphasis | must not |

| Titles of documents | Accounting in Business |

| Product names | Corel

WordPerfect |

| Variables in maths | E=mc² |

| Subtitles or headings | 42. How to get

started |

| Use of a letter as a word | Who knocked the L out of

London? |

| Decoration | FREE UPGRADE!!! |

Humans usually have no problem telling the difference

between these reasons, because they can read and understand

the meaning and context, and we’ve been exposed to many of

these meanings since we started to read. Computers cannot

(yet) do this reliably, so it has become conventional to use

descriptive names which make the distinction explicit, even

though the appearance may be the same.

LATEX has some of these built in, like

\emph, which provides

emphasis. This has a special feature

because when the surrounding text is

already italic, emphasis

automatically reverts to upright

type, which is the normal practice

in typesetting.

This has a special feature because {\itshape when

the surrounding text is already italic,

\emph{emphasis} automatically reverts to

\emph{upright type}}, which is the normal practice

in typesetting.This sensitivity to logic is programmed into

the definition of \emph and it’s not

hard to make up other commands of your own which could do

the same, such as \foreign or

\product.

But why would you bother? In a short document it’s

probably not important, but if you’re writing a long

report, or a formal document like an article, a book, or a

thesis, it makes writing and editing hugely easier if you

can control whole groups of special effects with a single

command, such as italicising, indexing, or cross-referencing

to a glossary. If a format needs changing, you only have to

change the definition, and every occurrence automatically

follows suit.

A warning from the past

Beware of this ‘vaine conceipt of simple men,

which judge things by ther effects, and not by ther

causes’. (Edmund Spenser, 1633)

It’s hugely more efficient and productive to have

control of the cause than the effect.

It also makes it possible to find and act on groups of

meanings — such as making an index of scientific names,

or retrieving all product names — if they are identified

as such. Otherwise you’d spend weeks hunting manually

through every \textit command to find the

ones you wanted. This is the bottom line of automation: it

can save you time and money.

In Chapter 7 ‘Programmability’ below we will see how to make your

own simple commands to do things like this.

6.2.7 Colour

You can typeset anything in LATEX in any colour you

want using the xcolor package. Adding the

command \usepackage{xcolor}

to your Preamble (note the US spelling of color) makes

available a default palette of primary colours: red, green, and blue for the RGB colour model used for emitted light

(computer and television screens), and cyan, magenta, yellow, and black for the

CMYK colour model used for reflected

light (printing).

Warning

This package supersedes the old

color package, which

SHOULD NOT be used, as

everything it did is now done by

xcolor.

For the occasional word or phrase in colour, use the

command \textcolor with two arguments, the

colour name and the text: \textcolor{red}{like this} to get red

like this. There is an

unscoped \color command as well, for use

within groups:

...{\color{blue}some text in blue}...There are several package options for additional

colours: two popular ones are dvipsnames,

which provides a 64-colour palette of predefined colour

names exactly matching the big box of 64

Crayola™ colouring pencils

much favoured by artists and designers; and

svgnames, which provides the 256 colours

defined in the specification for the Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) drawing

and diagramming language (which includes the 64 colours

of dvipsnames). There are others too: see the

documentation for the xcolor

package.

If you want the Crayola

colour Crimson, and you have loaded

xcolor with the svgnames or

dvipsnames option, you can use it as a

colour name (colour names are case-sensitive):

{\color{Crimson}some red text}

\textcolor{Crimson}{some red text}As some of the predefined

colour names are quite long, you can create a short name of

your own for colours you use frequently, using the

\definecolor command:

\definecolor{mb}{named}{MidnightBlue}The \definecolor command needs three

arguments: your shorthand name, the name of the colour

model, and the colour specification. In the case of the

named model, the last argument is one of

the colour names specified by the named option you loaded the

package with.

Using the \definecolor command, you

can also define any colour you want by giving it a name,

specifying which colour model, and providing the Red-Green-Blue (RGB) or Cyan-Magenta-Yellow-Black (CMYK) colour

values expressed as decimal fractions of 255,

separated by commas. For example, an

RGB colour given as (37,125,224) in

decimal integer form can be given as:

\definecolor{midblue}{rgb}{0.145,0.490,0.882}To get the fractional value, divide the integer

value by 255, the maximum for each of the hues in the

Red-Green-Blue colour model. You can then use

\textcolor with your new colour name:

midblue looks like this if

you’re reading in colour. Alternatively, use the

HTML hexadecimal colour model, the same

as used in web pages and CSS stylesheets:

\definecolor{midblue}{HTML}{250FE0}The xcolor package also provides

two colour versions of \fbox (see § 4.6.2 above) called

\colorbox and \fcolorbox

which create a box with a coloured background:

\colorbox{midblue}{\color{magenta}Magenta on midblue}The material in the second argument can have its own

text colour, as in the example. The

\fcolorbox has an extra first argument to

specify the colour of the frame or border placed around the

box. The border width is controlled by the \fboxrule setting and the

separation between rule and content is controlled by the

\fboxsep setting as we

already saw in § 4.6.2 above.

However, combining colours is an art and a skill: using

the command above to get the effect magenta on midblue illustrates why

it is important to learn about colour models and palettes

before trying to use them!

, and

, and