Originally a terminal was a screen and a keyboard, looking

very much like a standard desktop computer in the days before

flat screens and windowing systems. There are still a

surprising number of these around (see Figure B.1 above). The important point is that it was

(is) a text-only interface to the computer: no graphics. You

got 25 lines of 80 fixed-width white-on-black or

green-on-black characters, no fonts, no colours, and no mouse;

maybe reverse-video as a form of highlighting if you were

lucky.

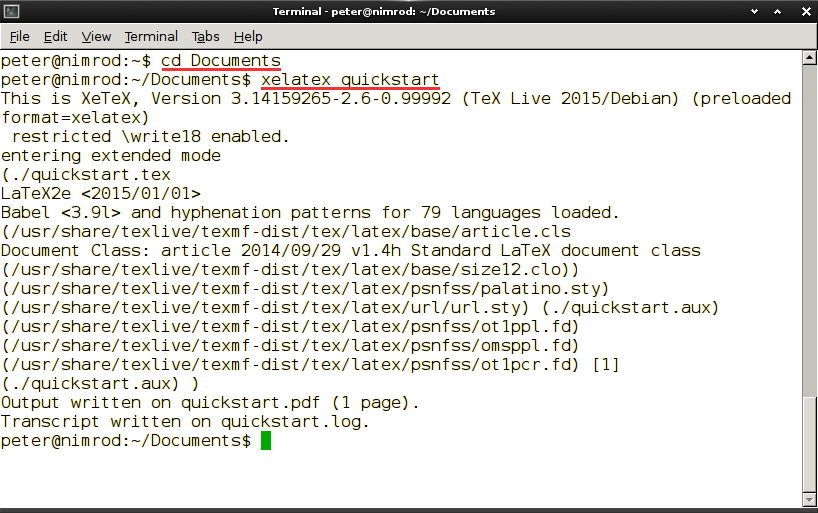

Nowadays the word ‘terminal’

usually means a ‘virtual terminal’: a window

that behaves like a terminal — 25 lines of 80 fixed-width

characters in monochrome (see Figure B.2 below). It’s a

window into the heart of your computer. Even though you still

have all your other windows visible, it knows nothing about

them and can’t interact with them (except for copy and paste).

But instead of being a padded cell, most terminals can do

things many other windows can’t, like handling files in bulk,

or to a schedule, or unattended, even forcing things to happen

even when the graphical world outside has got itself jammed

solid.

B.1.1 So where is the terminal window?

- Apple Macintosh OS X

Click on

;

- Microsoft Windows

Click on the Windows or Start button,

(in older versions it’s called , in some newer ones just

)

- Unix and GNU/Linux

Click on the menu

(in some systems it’s

in or it may be called

)

When you have finished using the terminal, it’s good

practice to type exit (and

press Enter). On Apple Macintosh OS X

systems you also have to click

on to make it close down properly.

B.1.2 Using the terminal window

On a physical terminal you usually have to log in first

(very much like today: username and password). In a terminal

window this isn’t usually necessary (see Figure B.2 below) because it’s inside your graphical

system, and you’ve already logged in to that.

Figure B.2: Virtual terminal in a window

In this example I’m logged into a computer called

nimrod with my username

peter. The system prompt is the

directory name plus a dollar sign (the tilde indicates

that I’m in my home directory system). For visibility, I

underlined in red here the commands I typed, one to

change to my Documents folder, and

one to run XƎLATEX on the

quickstart.tex document.

The first thing you see is the

prompt (usually a dollar sign or

percent sign, or maybe a greater-than pointer

C:\> like MS-DOS

used to use). When the prompt appears, you can type an

instruction (command) and press the Enter

key at the end of the line to send if off to the computer

for processing. Until you press Enter, the

computer has no idea you’ve finished typing: you

MUST press

Enter at the end of each line of command

for it to take effect.

The results, if any, are displayed on the screen, and

the prompt is displayed again ready for your next command.

Some commands don’t have any output: if you change directory

or delete a file, for example, you just get another prompt.

There’s no message confirming the action, and no check to

see if you really meant it. You said to do it, and it’s

done.