|

|

|||||

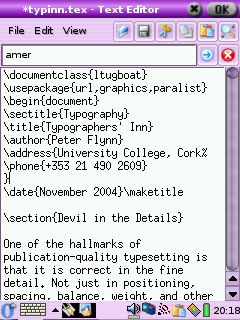

As we saw in Chapter 2, LATEX uses plain-text files, so they can be read and written by any standard application that can open text files. This helps preserve your information over time, as the plain-text format cannot be obsoleted or hijacked by any manufacturer or sectoral interest, and it will always be readable on any computer, from your handheld (yes, LATEX is available for some PDAs, see Figure 10.1) to the biggest supercomputer.

However, LATEX is intended as the last stage of the editorial process: formatting for print or display. If you have a requirement to re-use the text in some other environment — a database perhaps, or on the Web or a CD-ROM or DVD, or in Braille or voice output — then it should probably be edited, stored, and maintained in something neutral like the Extensible Markup Language (XML), and only converted to LATEX when a typeset copy is needed.

Although LATEX has many structured-document features in common with SGML and XML, it can still only be processed by the LATEX and pdfLATEX programs. Because its macro features make it almost infinitely redefinable, processing it requires a program which can unravel arbitrarily complex macros, and LATEX and its siblings are the only programs which can do that effectively. Like other typesetters and formatters (Quark XPress, PageMaker, FrameMaker, Microsoft Publisher, 3B2 etc.), LATEX is largely a one-way street leading to typeset printing or display formatting.

Converting LATEX to some other format therefore means you will unavoidably lose some formatting, as LATEX has features that others systems simply don't possess, so they cannot be translated — although there are several ways to minimise this loss. Similarly, converting other formats into LATEX often means editing back the stuff the other formats omit because they only store appearances, not structure.

However, there are at least two excellent systems for converting LATEX directly to HyperText Markup Language (HTML) so you can publish it on the web, as we shall see in section 10.2.

10.1 Converting into LATEX

10.1 Converting into LATEX

There are several systems which will save their text in LATEX format. The best known is probably the LYX editor (see Figure 2.1), which is a wordprocessor-like interface to LATEX for Windows and Unix. Both the AbiWord and Kword wordprocessors on Linux systems have a very good Save As...LATEX output, so they can be used to open Microsoft Word documents and convert to LATEX. Several maths packages like the EuroMath editor, and the Mathematica and Maple analysis packages, can also save material in LATEX format.

In general, most other wordprocessors and DTP systems either don't have the level of internal markup sophistication needed to create a LATEX file, or they lack a suitable filter to enable them to output what they do have. Often they are incapable of outputting any kind of structured document, because they only store what the text looks like, not why it's there or what role it fulfills. There are two ways out of this:

-

Use the → menu item to save the wordprocessor file as HTML, rationalise the HTML using Dave Raggett's HTML Tidy, and convert the resulting Extensible HyperText Markup Language (XHTML) to LATEX with any of the standard XML tools (see below).

-

Use a specialist conversion tool like EBT's DynaTag (supposedly available from Enigma, if you can persuade them they have a copy to sell you; or you may still be able to get it from Red Bridge Interactive in Providence, RI). It's expensive and they don't advertise it, but for bulk conversion of consistently-marked Word files into XML it beats everything else hands down. The Word files must be consistent, though, and must use named styles from a stylesheet, otherwise no system on earth is going to be able to guess what it means.

There is of course a third way, suitable for large volumes only: send it off to the Pacific Rim to be retyped into XML or LATEX. There are hundreds of companies from India to Polynesia who do this at high speed and low cost with very high accuracy. It sounds crazy when the document is already in electronic form, but it's a good example of the problem of low quality of wordprocessor markup that this solution exists at all.

You will have noticed that most of the solutions lead to one place: SGML1 or XML. As explained above and elsewhere, these formats are the only ones devised so far capable of storing sufficient information in machine-processable, publicly-accessible form to enable your document to be recreated in multiple output formats. Once your document is in XML, there is a large range of software available to turn it into other formats, including LATEX. Processors in any of the common SGML/XML processing languages like the Document Style Semantics and Specification Language (DSSSL), the Extensible Stylesheet Language [Transformations] (XSLT), Omnimark, Metamorphosis, Balise, etc. can easily be written to output LATEX, and this approach is extremely common.

Much of this will be simplified when wordprocessors support native, arbitrary XML/XSLT as a standard feature, because LATEX output will become much simpler to produce.

-

Sun's Star Office and its Open Source sister, OpenOffice, have used XML as their native file format for several years, and there is a project at the Organisation for the Advancement of Structured Information Systems (OASIS) for developing a common XML office file format based on those used by these two packages, which has been proposed to the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) in Geneva as a candidate for an International Standard.

-

WordPerfect has also had a native SGML (and now XML) editor for many years, which will work with any Document Type Definition (DTD) (but not a Schema; and at the time of writing (2005) it still used a proprietary stylesheet format).

-

Microsoft has had a half-hearted ‘Save As...XML’ for a while, using an internal and formerly largely undocumented Schema (recently published at last). The ‘Professional’ versions of Word and Excel in Office 11 (Office 2003 for XP) now have full support for arbitrary Schemas and a real XML editor, albeit with a rather primitive interface, but there is no conversion to or from Word's

.docformat.2However, help comes in the shape of Ruggero Dambra's WordML2LATEX, which is an XSLT stylesheet to transform an XML document in this internal Schema (WordML) into LATEXε format. Download it from any CTAN server in

/support/WordML2LaTeX. -

Among the conversion programs on CTAN is Ujwal Sathyam's rtf2latex2e, which converts Rich Text Format (RTF) files (output by many wordprocessors) to LATEXε. The package description says it has support for figures and tables, equations are read as figures, and it can the handle the latest RTF versions from Microsoft Word 97/98/2000, StarOffice, and other wordprocessors. It runs on Macs, Linux, other Unix systems, and Windows.

When these efforts coalesce into generalised support for arbitrary DTDs and Schemas, it will mean a wider choice of editing interfaces, and when they achieve the ability to run XSLT conversion into LATEX from within these editors, such as is done at the moment with Emacs or XML Spy, we will have full convertability.

- The Standard Generalized Markup Language (SGML) itself is little used now for new projects, as the software support for its daughter XML is far greater, but there are still hundreds of large document repositories in SGML still growing their collection by adding documents.

- Which is silly, given that Microsoft used to make one of the best Word-to-SGML converters ever, which was bi-directional (yes, it could round-trip Word to SGML and back to Word and back into SGML). But they dropped it on the floor when XML arrived.

10.1.1 Getting LATEX out of XML

10.1.1 Getting LATEX out of XML

Assuming you can get your document out of its wordprocessor format into XML by some method, here is a very brief example of how to turn it into LATEX.

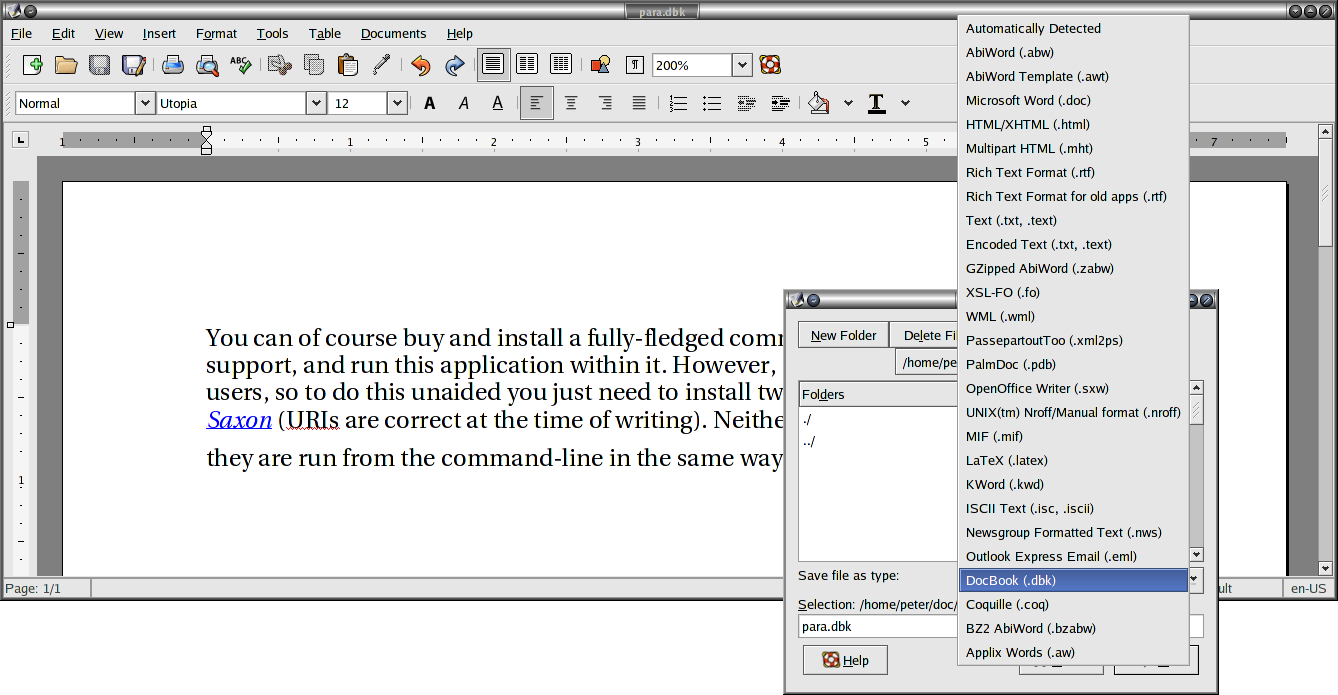

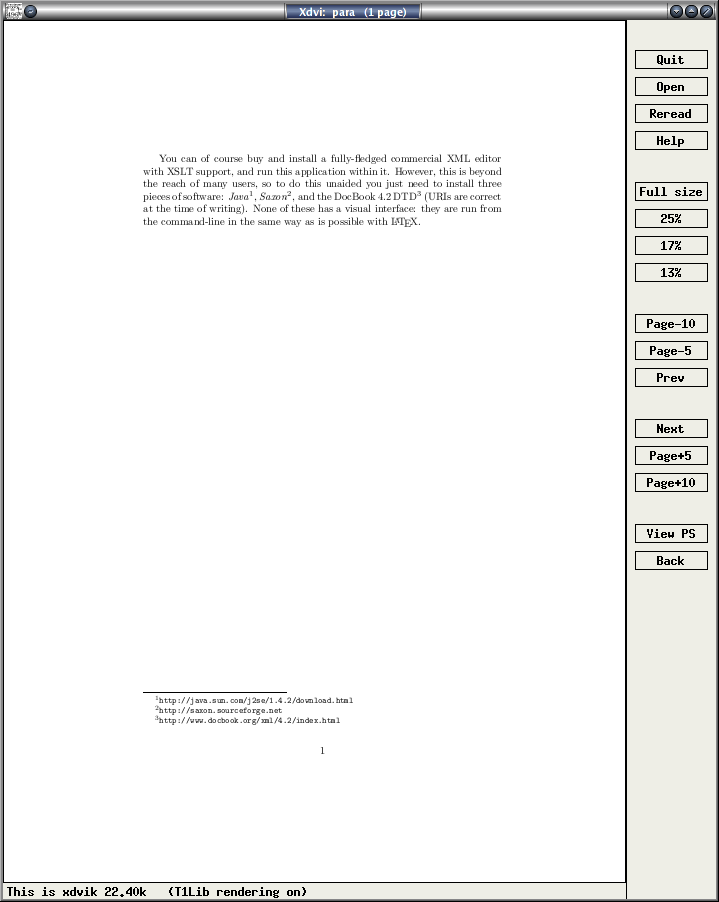

You can of course buy and install a fully-fledged commercial XML editor with XSLT support, and run this application within it. However, this is beyond the reach of many users, so to do this unaided you just need to install three pieces of software: Java, Saxon and the DocBook 4.2 DTD (URIs are correct at the time of writing). None of these has a visual interface: they are run from the command-line in the same way as is possible with LATEX.

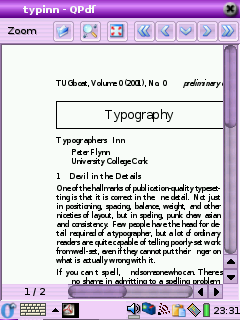

As an example, let's take the above paragraph, as typed or imported into AbiWord (see Figure 10.1). This is stored as a single paragraph with highlighting on the product names (italics), and the names are also links to their Internet sources, just as they are in this document. This is a convenient way to store two pieces of information in the same place.

AbiWord can export in DocBook format, which is an XML vocabulary for describing technical (computer) documents–it's what I use for this book. AbiWord can also export LATEX, but we're going make our own version, working from the XML (Brownie points for the reader who can guess why I'm not just accepting the LATEX conversion output).

Although AbiWord's default is to output an XML book document type, we'll convert it to a LATEX article document class. Notice that AbiWord has correctly output the expected section and title markup empty, even though it's not used. Here's the XML output (I've changed the linebreaks to keep it within the bounds of this page size):

<!DOCTYPE book PUBLIC "-//OASIS//DTD DocBook XML V4.2//EN"

"http://www.oasis-open.org/docbook/xml/4.2/docbookx.dtd">

<book>

<!-- ===================================================================== -->

<!-- This DocBook file was created by AbiWord. -->

<!-- AbiWord is a free, Open Source word processor. -->

<!-- You may obtain more information about AbiWord at www.abisource.com -->

<!-- ===================================================================== -->

<chapter>

<title></title>

<section role="unnumbered">

<title></title>

<para>You can of course buy and install a fully-fledged commercial XML

editor with XSLT support, and run this application within it. However, this

is beyond the reach of many users, so to do this unaided you just need to

install three pieces of software: <ulink

url="http://java.sun.com/j2se/1.4.2/download.html"><emphasis>Java</emphasis></ulink>,

<ulink

url="http://saxon.sourceforge.net"><emphasis>Saxon</emphasis></ulink>, and

the <ulink url="http://www.docbook.org/xml/4.2/index.html">DocBook 4.2 DTD</ulink>

(URIs are correct at the time of writing). None of these has a visual

interface: they are run from the command-line in the same way as is possible

with L<superscript>A</superscript>T<subscript>E</subscript>X.</para>

</section>

</chapter>

</book>

The XSLT language lets us create templates for each type of element in an XML document. In our example, there are only three which need handling, as we did not create chapter or section titles (DocBook requires them to be present, but they don't have to be used).

-

para, for the paragraph[s];

-

ulink, for the URIs;

-

emphasis, for the italicisation.

I'm going to cheat over the superscripting and

subscripting of the letters in the LATEX logo, and use my

editor to replace the whole thing with the

\LaTeX command. In the other three cases,

we already know how LATEX deals with these, so we can

write our templates (see Figure 10.2).

|

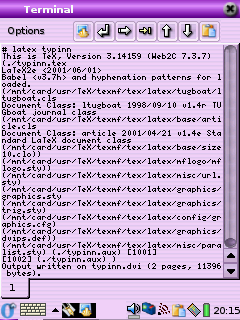

If you run this through Saxon, which is an XSLT processor, you can output a LATEX file which you can process and view (see Figure 10.3).

$ java -jar /usr/local/saxonb8-0/saxon8.jar -o para.ltx \ para.dbk para.xsl $ latex para.ltx This is TeX, Version 3.14159 (Web2C 7.3.7x) (./para.ltx LaTeX2e <2001/06/01> Loading CZ hyphenation patterns: Pavel Sevecek, v3, 1995 Loading SK hyphenation patterns: Jana Chlebikova, 1992 Babel <v3.7h> and hyphenation patterns for english, dumylang, nohyphenation, czech, slovak, german, ngerman, danish, spanish, catalan, finnish, french, ukenglish, greek, croatian, hungarian, italian, latin, mongolian, dutch, norwegian, polish, portuguese, russian, ukrainian, serbocroat, swedish, loaded. (/usr/TeX/texmf/tex/latex/base/article.cls Document Class: article 2001/04/21 v1.4e Standard LaTeX document class (/usr/TeX/texmf/tex/latex/base/size10.clo)) (/usr/TeX/texmf/tex/latex/ltxmisc/url.sty) (./para.aux) [1] (./para.aux) ) Output written on para.dvi (1 page, 1252 bytes). Transcript written on para.log. $ xdvi para &

|

Writing XSLT is not hard, but

requires a little learning. The output method here is

text, which is LATEX's file

format (XSLT can also output

HTML and other formats of

XML).

-

The first template matches ‘

/’, which is the document root (before the book start-tag). At this stage we output the text\documentclass{article}and\usepackage{url}. The ‘apply-templates’ instructions tells the processor to carry on processing, looking for more matches. XML comments get ignored, and any elements which don't match a template simply have their contents passed through until the next match occurs. -

The book template outputs the

\begin{document}and the\end{document}commands, and between them to carry on processing. -

The para template just outputs its content, but follows it with a linebreak (using the hexadecimal character code

x000A(see the ASCII chart in Table C.1). -

The ulink template outputs its content but follows it with a footnote using the

\urlcommand to output the value of the url attribute. -

The emphasis template surrounds its content with

\emph{and}.

This is a relatively trivial example, but it serves to show that it's not hard to output LATEX from XML. In fact there is a set of templates already written to produce LATEX from a DocBook file at http://www.dpawson.co.uk/docbook/tools.html#d4e2905

10.2 Converting out of LATEX

10.2 Converting out of LATEX

This is much harder to do comprehensively. As noted earlier, the LATEX file format really requires the LATEX program itself in order to process all the packages and macros, because there is no telling what complexities authors have added themselves (what a lot of this book is about!).

Many authors and editors rely on custom-designed or homebrew converters, often written in the standard shell scripting languages (Unix shells, Perl, Python, Tcl, etc). Although some of the packages presented here are also written in the same languages, they have some advantages and restrictions compared with private conversions:

-

Conversion done with the standard utilities (eg awk, tr, sed, grep, detex, etc) can be faster for ad hoc translations, but it is easier to obtain consistency and a more sophisticated final product using LATEX2HTML or TEX4ht — or one of the other systems available.

-

Embedding additional non-standard control sequences in LATEX source code may make it harder to edit and maintain, and will definitely make it harder to port to another system.

-

Both the above methods (and others) provide a fast and reasonable reliable way to get documents authored in LATEX onto the Web in an acceptable — if not optimal — format.

-

LATEX2HTML was written to solve the problem of getting LATEX-with-mathematics onto the Web, in the days before MathML and math-capable browsers. TEX4ht was written to turn LATEX documents into Web hypertext — mathematics or not.

10.2.1 Conversion to Word

10.2.1 Conversion to Word

There are several programs on CTAN to do LATEX-to-Word and similar conversions, but they do not all handles everything LATEX can throw at them, and some only handle a subset of the built-in commands of default LATEX. Two in particular, however, have a good reputation, although I haven't used either of them (I stay as far away from Word as possible):

-

latex2rtf by Wilfried Hennings, Fernando Dorner, and Andreas Granzer translates LATEX into RTF — the opposite of the rtf2latex2e mentioned in the 4th item. RTF can be read by most wordprocessors, and this program preserves layout and formatting for most LATEX documents using standard built-in commands.

-

KirillA Chikrii's TEX2Word for Microsoft Windows is a converter plug-in for Word to let it open TEX and LATEX documents. The author's company claims that ‘virtually any existing TEX/LATEX package can be supported by TEX2Word’ because it is customisable.

One easy route into wordprocessing, however, is the reverse of the procedures suggested in the preceding section: convert LATEX to HTML, which many wordprocessors read easily. The following sections cover two packages for this.

10.2.2 LATEX2HTML

10.2.2 LATEX2HTML

As its name suggests, LATEX2HTML is a system to convert LATEX structured documents to HTML. Its main task is to reproduce the document structure as a set of interconnected HTML files. Despite using Perl, LATEX2HTML relies very heavily on standard Unix facilities like the NetPBM graphics package and the pipe syntax. Microsoft Windows is not well suited to this kind of composite processing, although all the required facilities are available for download in various forms and should in theory allow the package to run — but reports of problems are common.

-

The sectional structure is preserved, and navigational links are generated for the standard Next, Previous, and Up directions.

-

Links are also used for the cross-references, citations, footnotes, ToC, and lists of figures and tables.

-

Conversion is direct for common elements like lists, quotes, paragraph-breaks, type-styles, etc, where there is an obvious HTML equivalent.

-

Heavily formatted objects such as math and diagrams are converted to images.

-

There is no support for homebrew macros.

There is, however, support for arbitrary hypertext links, symbolic cross-references between ‘evolving remote documents’, conditional text, and the inclusion of raw HTML. These are extensions to LATEX, implemented as new commands and environments.

LATEX2HTML outputs a directory named after the input filename, and all the output files are put in that directory, so the output is self-contained and can be uploaded to a server as it stands.

10.2.3 TEX4ht

10.2.3 TEX4ht

TEX4ht operates differently from LATEX2HTML: it uses the TEX program to process the file, and handles conversion in a set of postprocessors for the common LATEX packages. It can also output to XML, including Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) and DocBook, and the OpenOffice and WordXML formats, and it can create TEXinfo format manuals.

By default, documents retain the single-file structure implied by the original, but there is again a set of additional configuration directives to make use of the features of hypertext and navigation, and to split files for ease of use.

10.2.4 Extraction from PS and PDF

10.2.4 Extraction from PS and PDF

If you have the full version of Adobe Acrobat, you can open a PDF file created by pdfLATEX, select and copy all the text, and paste it into Word and some other wordprocessors, and retain some common formatting of headings, paragraphs, and lists. Both solutions still require the wordprocessor text to be edited into shape, but they preserve enough of the formatting to make it worthwhile for short documents. Otherwise, use the pdftotext program to extract everything from the PDF file as plain (paragraph-formatted) text.

10.2.5 Last resort: strip the markup

10.2.5 Last resort: strip the markup

At worst, the detex program on CTAN will strip a LATEX file of all markup and leave just the raw unformatted text, which can then be re-edited. There are also programs to extract the raw text from DVI and PostScript (PS) files.