Images (graphics) can be included anywhere in a LATEX

document, although in most cases of formal documents they will

occur in Figures (see § 4.3 above). To use graphics, you

need to use the graphicx package in

your Preamble:

\usepackage{graphicx}. This package provides the command

\includegraphics which is used to insert an

image in a document. The command is followed by the name of

your graphics file usually without the filetype

(we’ll see in the last listitem ‘LATEX will search for the graphic …’ below

why you don’t normally need to include the filetype).

\includegraphics{myhouse}In most cases you should just make sure the image file is

in the same folder (directory) as the document you use it in.

This avoids a lot of messing around remembering where you put

the files; but you could instead put them all in a single

subfolder (for example, called images)

and include that as part of the filename you use in the

command.

\includegraphics{images/myhouse}If you have images you want to use in several

different documents in different places on your disk, there is

a way to tell LATEX where to look (see § 4.4.4 below).

4.4.1 Supported image file formats

The type of image file you use depends on LATEX

processor you are using (see § 1.3 above

for how to choose). The common file types are:

JPG (Joint Photographic

Experts Group), used for photographs and

scanned images;

PNG (Portable Network

Graphic), used for photographs and scanned

images;

PDF (Portable Document

Format), used for vector graphics (drawings,

diagrams) and typographic output from other

programs;

EPS (Encapsulated

Postscript), an old publishing industry

standard for many years, and the forerunner of

PDF, still used by some older

programs that generate diagrammatic or typographic

output.

See § 4.4.1.1 below and § 4.4.1.2 below for other file formats. For more

details, see the answers to the question on StackExchange,

Which

graphics formats can be included in documents processed by

latex or pdflatex? Basically, for modern systems

running XƎLATEX, LuaLATEX or

pdflatex (creating

PDF output) graphics files

MAY be in

PNG, PDF, or

JPG (JPEG) format

ONLY. (You may come across

very old systems running plain (original) LATEX (creating

DVI output) in which graphics files

MUST be in

EPS format

ONLY: no other format will

work: see § 4.4.1.2 below)

PNG actually gets converted to

the PDF internal format automatically

(at a small penalty in terms of speed) so for lots of

images, or very large images, use JPG

format or preconvert them to PDF;

It is also of course possible to convert (repackage)

your JPG pictures to

PDF, using any of the standard

graphics conversion/manipulation programs (see § 4.4.1.1 below for details). Preconverting all

your images to PDF makes them load

into your document slightly faster.

LATEX will search for the graphic file by file

type, in this order (check for the newest definition in

your pdftex.def):

.png, .pdf,

.jpg, .mps,

.jpeg, .jbig2,

.jb2, .PNG,

.PDF, .JPG,

.JPEG, .JBIG2,

and .JB2.

See § 4.4.3 below for more

about how to create and manage your image files.

4.4.1.1 Other file formats

Convert them to one of the supported formats using a

graphics editing or conversion tool such as the GNU

Image Manipulation Program (GIMP), the NetPBM

utilities, ImageMagick,

or a utility like Péter Szabó’s sam2p

(not available with TEX Live but downloadable for

Windows and Linux).

Some commercial distributions of TEX systems allow

other formats to be used, such as GIF,

Microsoft Bitmap (BMP), or

Hewlett-Packard’s Printer Control

Language (PCL) files, and others, by using

additional conversion software provided by the supplier;

but you cannot send such documents to other LATEX users

and expect them to work if they don’t have the same

distribution installed as you have.

It is in fact possible to tell LATEX to generate the

right file format by itself during processing, but this

uses an external graphics converter like one of the above,

and as it gets done afresh each time, it may slow things

down.

4.4.1.2 Postscript

Since TEX 2010, EPS files will be

automatically converted to PDF if you

include the epstopdf package. This

avoids need to keep your graphics in two formats, at the

expense of a longer compile time while it converts every

EPS image (not recommended).

All good graphics packages (eg

GIMP,

PhotoShop, Corel

Draw, etc) can save images as

EPS, but be very careful with other

software such as statistics, engineering, mathematical,

and numerical analysis packages, because some of them,

especially on Microsoft Windows platforms, use a very poor

quality driver, which in turn creates very poor quality

EPS files. If in doubt, check with an

expert. If you find an EPS graphic

doesn’t print, the chances are it’s been badly made by the

creating software. Downloading Adobe’s own Postscript

driver from their Web site and using that instead may

improve things, but the only real solution is to use

software that creates decent output.

For these reasons, if you create vector

EPS graphics, and convert them to

PDF format, do not

keep additional JPG or

PNG copies of the same image in the

same directory, because they risk being used first by

LATEX instead of the PDF file,

because of the order in which it searches.

EPS files, especially bitmaps, can

be very large indeed, because they are stored in

ASCII format. Staszek Wawrykiewicz has drawn my

attention to a useful MS-DOS program to

overcome this, called cep

(‘Compressed Encapsulated PostScript’)

available from CTAN archive in the

support/pstools

directory, which can compress EPS files

to a fraction of their original size. The original file

can be replaced by the new smaller version and still used

directly with \includegraphics.

One final warning about using EPS

files with \includegraphics: never try

to specify an absolute path (one beginning with a slash)

or one addressing a higher level of directory (one

beginning with ../). The

dvips driver will not accept

these because they pose a security risk to

PostScript documents. Unlike

PDF,

PostScript is a real

programming language, capable of opening and deleting

files, and the last thing you want is to create a document

able to mess with your filesystem (or someone

else’s).

4.4.2 Resizing images

The \includegraphics command can take

optional arguments within square brackets before the

filename to specify the height or width, as in the example

below. This will resize the image that prints; whichever

dimension you specify (height or width) the other dimension

will automatically be scaled in proportion to preserve the

aspect ratio.

The file on disk does not get changed in any way, and

nor does the copy included inside the PDF:

what gets changed is just the size that it displays at in

the finished document. So if you include a huge

JPG but tell LATEX to print it at a

small size, your PDF will still include

the whole image file at full size — all that changes is

the way it shows it. This is very inefficient: normally you

should create images at the right size for the

document.

If you specify both height and

width, the image will be distorted to fit (not really useful

except for special effects). You can scale an image by a

factor (using the scaled option) instead of

specifying height or width; clip it to specified

coordinates; or rotate it in either direction. Multiple

optional arguments are separated with commas.

For details of all the arguments, see the documentation

on the graphicx package or a copy of the

Companion. The

package also includes commands to

rotate,

mirror,

and scale text

as well as images.

4.4.3 Making images

There are two types of image: bitmaps and

vectors.

- Bitmaps

Bitmap images are made of coloured dots, so if you

enlarge them, they go jagged at the edges, and if you

shrink them, they may go blurry. Bitmaps are fine for

photographs, where every tiny dot is a different

colour, and the eye won’t notice so long as you

don’t shrink or enlarge too much. Bitmaps for

diagrams and drawings, however, are almost always the

wrong choice, and often disastrously bad.

- Vectors

Vector drawings are made from instructions, just

like LATEX is, but using a different language (eg

‘draw this from here to here, using a line this

thick’). They can be enlarged or reduced as

much as you like, and never lose accuracy, because

they get redrawn automatically at

any size. You can’t do photographs as vectors,

but vectors are the only acceptable method for drawings

or diagrams.

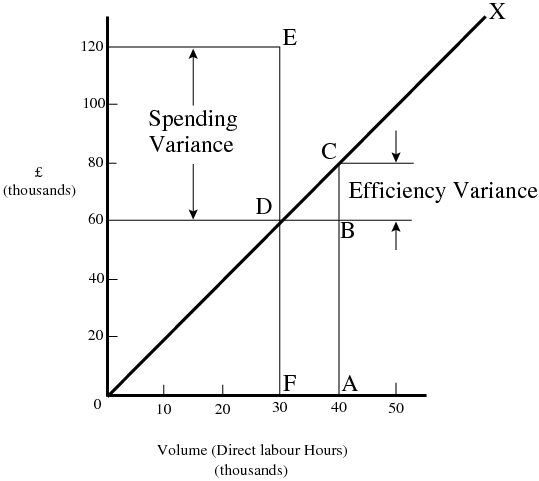

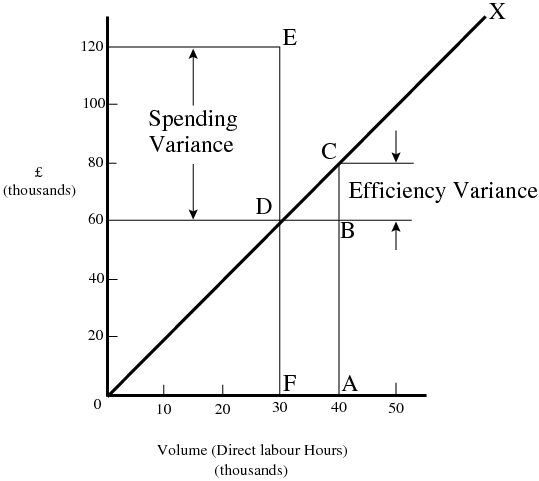

Figure 4.4: The vector diagram shrunk and enlarged

Vector graphic packages are also better suited for

saving your image directly in EPS or

PDF format (both of which use their own

vector language internally). All the major

graphics-generating packages in all disciplines output

vector formats: AutoCAD,

ChemDraw,

MathCAD,

Maple,

Mathematica,

ArcInfo, and so on.

EPS was for decades the

universally-accepted format for creating vector graphics for

publication, with PDF a close second.

PDF is now the most common format, but

most of the major graphics (drawing) packages can still save

as EPS, such as

PhotoShop, PaintShop

Pro, Adobe

Illustrator, Corel

Draw, and

GIMP. There are also some free

vector plotting and diagramming packages available like

InkScape,

tkPaint, and

GNUplot which do the same. Never,

ever (except in the direst necessity) create any

diagram as a bitmap.

Bitmap formats like JPG and

PNG are ideal for photographs, as they

are also able to compress the data substantially without too

much loss of quality. However, compressed formats are bad

for screenshots, if you are documenting computer tasks,

because too much compression makes them blurry. The popular

Graphics Interchange Format (GIF)

is good for screenshots, but is not supported by TEX: use

PNG instead, with the compression turned

down to minimum.

Avoid uncompressible formats like

BMP as they produce enormous and

unmanageable files. The Tagged Image

File Format (TIFF), popular with graphic designers,

should also be avoided if possible, partly because it is

even vaster than BMP, and partly because

far too many companies have designed and implemented

non-standard, conflicting, proprietary extensions to the

format, making it virtually useless for transfer between

different types of computers (except in faxes, where

it’s still used in a much stricter version).

Exercise 4.5 — Adding pictures

Add \usepackage{graphicx} to the

Preamble of your document, and copy or download an image

you want to include. Make sure it is a

JPG, PNG, or

PDF image.

Add \includegraphics and the

filename in curly braces (without the filetype), and

process the document and preview or print it.

Make it into a figure following the example in § 4.3 above.

4.4.4 Graphics storage

I mentioned earlier that there was a way to tell

LATEX where to look if you want to store some images centrally

for use in many different documents.

If you want to be able to use some images from any of

your LATEX documents, regardless of the folder[s], then

you should store the images in the subdirectory called

tex/generic within your Personal TEX Directory.

Otherwise, you can use the

command \graphicspath with a list

of one or more names of additional directories

you want searched when a file uses the

\includegraphics command.

Put each path in its own pair of curly braces within the

curly braces of the \graphicspath command.

I’ve used the ‘safe’

(MS-DOS) form of the Windows My

Pictures folder in the example here because you

should never use directory or file names containing spaces

(see the sidebar ‘Picking suitable filenames’ above).

Using \graphicspath does make your

file less portable, though, because file paths tend to be

specific both to an operating system and to your computer,

like the examples above.

\graphicspath{{c:/mypict~1/camera}{z:/corp/imagelib}}

\graphicspath{{/var/lib/images}{/home/peter/Pictures}}If you use original LATEX and

dvips to print or create

PostScript files, be aware that some versions will not by

default handle EPS files which are

outside the current directory, and will issue the error

message saying that it is ‘unable to find’

the image. As we mentioned above, this is because PostScript

is a programming language, and it would theoretically be

possible for a maliciously-made image to contain code which

might compromise your system. The decision to restrict

operation in this way has been widely criticised, but it

seems unlikely to be changed. If you are certain that your

EPS files are kosher, use the

R0 option in your command, eg

dvips -R0 ...

dvifile